An Interview with James Fitzpatrick

Originally published @ Film Music Review – An online e-zine since 1998

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor and publisher Roger Hall

Over the past four years, you have many Sammy Awards for “Excellence” with your outstanding work with the Tadlow Music label. How did that record label get started and how did you decide which film soundtracks to record first?

Because of the success of the contracting business, I decided to set up my own small label, to record every once in a while a score that I particularly loved… profits allowing. And, as being brought up in the 60’s, my choices very much centered around childhood favourites like THE GUNS OF NAVARONE, EXODUS, EL CID, TRUE GRIT and THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES. And this year I fulfilled dual ambitions of recording THE ALAMO (for Prometheus Records) and the complete LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, which had always been a lifetime ambition as LAWRENCE was the very first film I ever saw in the cinema!

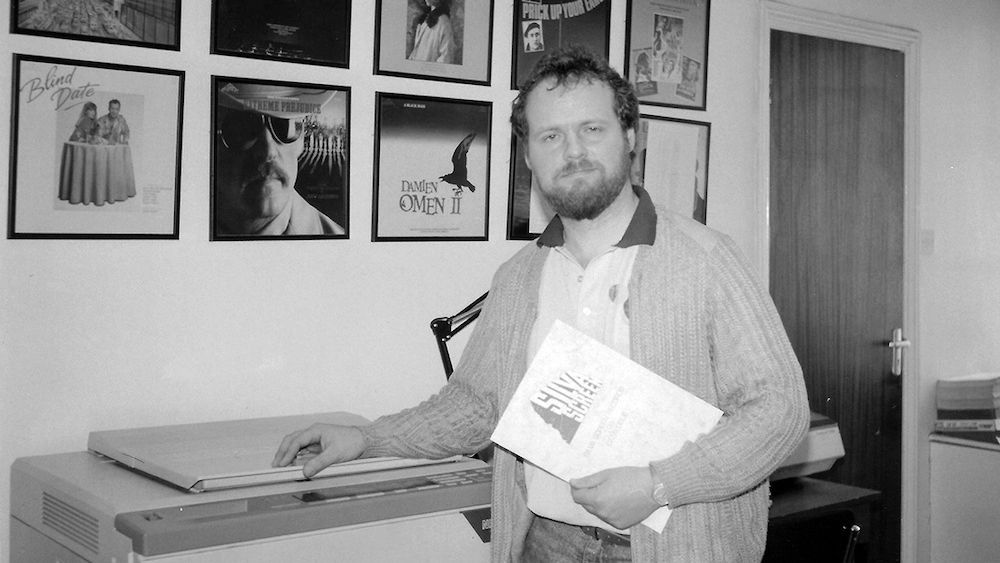

You are a highly respected and prolific album producer of numerous CD releases. Please tell about your beginning years as a producer at Silva Screen Records and how it developed from then on.

I started in the “music business” in 1973, straight after college, basically by mistake as I should have gone on to read Law at university, but took a year “off” exams by working in a record store. One thing led to another and I found myself managing a specialist Film and Show music shop in Soho in London in the late 70’s, that was 58 DEAN STREET RECORDS.

Then around 1983 I formed SILVA SCREEN RECORDS with Reynold D’Silva. Our goal was to release soundtrack albums that were not available in Europe. This proved successful especially with albums like CROCODILE DUNDEE that we decided to also record some of our favourite classic scores. Early recordings that I was “executive producer” on were THE BIG COUNTRY, LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and MUSIC FROM HAMMER HORROR FILMS, all performed by The Philharmonia Orchestra and recorded in London. However I was not too happy with some of these recordings, as certain production decisions were made at the sessions that I did not agree with, plus in London there are 2 recording rates. The first being the “Album Rate” in which the fee paid to musicians just covers the use of the recording in that particular album. In other words you do not own the recording 100%. In order to own the master rights you have to pay the much higher “Buyout Rate”. As a small record label this is something that we simply could not afford but we needed a buyout rate as actual album sales could not justify the recording costs , and we needed to be able to license the music for other usages like in commercials, film trailers, etc…

So I started to look around Europe for an orchestra that would be more economical to record but who also had the quality of London musicians, and with whom I could have greater artistic control and freedom (It is only really in USA and UK that they have this difference in recording rates… most other countries just have one simple buyout fee). Composer friend Carl Davis had just come back from recording his score for THE TRIAL in 1988 in Prague and raved about the musicians. So in February 1989 I set off to Prague with conductor Derek Wadsworth and music associate Nic Raine, to record an album of the Nino Rota music from all the Fellini films. Apart from the cold we had such a great time at the recording that I have been recording in Prague ever since.

From 1989 to 2000 I spent most of my time in Prague recording albums for Silva Screen Records: some were out and out commercial titles like BOND BACK IN ACTION, MUSIC FROM THE FILMS OF ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, GREATEST WESTERN THEMES etc., while other titles were of the “labour of love” variety like THE LAST VALLEY, THE LION IN WINTER, THE FILM MUSIC OF JEROME MOROSS.

Then around 2000 I decided to get out of the mainstream record industry as I saw the way business is going downhill, and set up my own music contracting company TADLOW MUSIC. The term Music Contractor can seem a little vague, in England a contractor is called a Fixer. This is a more accurate description as I “fix” orchestral recording sessions for clients in both London and Prague. So, basically, if a client or a composer or a producer needs to record an orchestra for either an album, film score, TV score or Video Game then I handle the booking of the musicians, studio, engineer etc., and often produce the recording sessions. In this capacity I have been fortunate to work with many wonderful composers including Rachel Portman,Kevin Kiner, Carl Davis, Guy Farley, Mark Thomas, Elmer Bernstein and Maurice Jarre.

You mentioned in your CD sleeve notes that you knew Maurice Jarre for many years. Did he ever tell you how he was hired to work with David Lean on LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and anything unusual about how the score was composed or first recorded?

Maurice told me many stories about the recording of LAWRENCE... mostly far too long to go into now as they would fill a small book, but Maurice did tell me the way that producer Sam Spiegel liked to approach different composers and make promises that he knew would never be fulfilled.

David Lean's original choices were of course Malcolm Arnold and his great friend William Walton. The rough cut of movie was screened to Malcolm Arnold and William Walton... but apparently they were both a little tiddly from too much wine at lunch, and thought the movie was just one long travelogue and David Lean overheard their comments and, depending upon whose account of the matter you read, they either declined to score the movie or were not even offered it. So then Sam started approaching many other composers including Benjamin Britten (he felt he needed a year to compose the music) Aram Khachaturian (he wasn’t able to leave Russia) and even musical composer Richard Rodgers, who even composed a “Love Theme from Lawrence of Arabia“... so it was obvious that he hadn’t quite got the idea of the movie!

In the meantime Spiegel also approached the little known French composer, Maurice Jarre to write some of the ethnic music cues because Maurice had recently scored SUNDAYS AND CYBELE which utilized Tibetan music... although this was library music that Maurice hadn’t even composed. In Maurice’s own words : “When I arrived in London there was still great uncertainly as to who was going to score the movie as Spiegel was still “negotiating“ with bigger name composers, so in my first few weeks there I just sketched out a small amount of music as nobody really knew which sections of the movie I would be scoring. At that point David Lean hadn’t spoken to me apart from “Hello“ and “How are you?“ etc. One day Sam suddenly called me into his office and asked if I had actually written anything for the film. I said “sure“ and started to play a theme, which later became the music of the main LAWRENCE theme, on the piano. David Lean was there and suddenly jumped up, came over to me and put his hand on my shoulder and said to Sam “This chap seems to know exactly what I want and understands the music for LAWRENCE OF ARABIA... maybe he should do all the score?“ Sam turned to me and said “Well, Maurice, you have six weeks to write and record the music!“

But even after Maurice had been asked to compose the score it appears that Spiegel was still negotiating with other composers as he was obviously worried that such an inexperienced composer might not be able to complete the task in time for the premiere of the movie. It seems that one of the other composers approached at this time was Gerard Schurmann... who was in fact offered co-composing. Gerard’s account published in The Cue Sheet in 1990 is very detailed about the whole affair and differs quite dramatically from Maurice’s own account, also featured in The Cue Sheet in April 1990. I certainly would not be the person to question either account, as I was not there. So maybe it is best to leave this chapter alone except to say that obviously Maurice and Gerard did not “hit it off“ and Maurice was not happy with the orchestrations and Gerard was less than pleased with the standard and detail of the compositional sketches he was being given.

Maurice also told me about working with Adrian Boult on the score. He recalled: “At that time in the British Film Industry there was what was called the Eady plan, whereby the government would grant certain subsidies or tax breaks as long as a high percentage of British technicians were used on the movie. Sam Spiegel knew that I wanted to conduct but he wanted (and needed) and additional British credit on the music budget. As the orchestra booked for the scoring was The London Philharmonic Orchestra then Sam said he wanted Sir Adrian Boult to conduct. I thought this was wonderful as he was a fabulous conductor and I had great admiration for him. On the day of the recording sessions he rehearsed the first cue with the orchestra, but when it came to the actual “take“ I advised him about the streamers coming across the screen and how he had to be in sync with these and the tempo markings on the score. At this he began to give me a totally blank look and said that he had no idea what I was talking about! Apparently Sir Adrian hadn’t conducted a film score in this way and he explained to Sam that he was not experienced in this and he said to Sam “This young chap you have here seems to know how to do it. So from that point I conducted all the music, but Sir Adrian got the screen credit“.

It would seem that Sir Adrian did record versions of “The Overture“ and “The Voice of the Guns“, as two quite different performances of these cues appeared on the special LP and Souvenir Brochure box-set edition which did not feature on any other edition of the soundtrack that appeared in 1962. But these were also re-recorded with Jarre conducting. It also appears that the London Philharmonic Orchestra at some stage in the recording had to be replaced with session musicians organized by Gerard Schurmann and his contractor Phil Jones, as both Jarre and Schurmann felt the orchestra were not really quite up to the more complicated cues. Having recorded the score twice I can vouch that some of the cues are the most difficult to record both from a performance standpoint and just getting a balanced sound.

Maurice was certainly less than happy with the re-recording I did for Silva Screen a few years ago. And I don’t blame him as just about everything that could go wrong on a series of sessions did, but Maurice put the blame (in his interview in the Cue Sheet) on my choice of studios...CTS Wembley. However, this is not correct, as my choice all along had been to record LAWRENCE at Abbey Road studios with Mike Ross-Trevor... but the production was “hi-jacked“ in my view by Christopher Palmer who insisted that Maurice would be far happier recording at CTS Studios with Dick Lewzey engineer. This certainly was never my choice... but I was overruled by Christopher, who also took it upon himself (with he said Maurice’s blessing) to change some of the orchestrations and make edits that to me did not make sense. So the recording didn’t turn out as either Maurice or myself wanted... it would have been so much better at Abbey Road and maybe would have saved me a fortune having to record the whole score all over again.

Fortunately I met Maurice in Seville a few months after the CTS sessions and he said to me in his most charming way “James, that recording you did is really sheety!... but the booklet and artwork are superb“. So we still remained friends and could laugh about it, especially as I did make a promise to “have another go at Lawrence“ but this time with the orchestra, studio and engineer of my choice.

Did Maurice Jarre ever mention his desire to record the complete score and why do you think it has taken so long to record the complete LAWRENCE OF ARABIA?

Mainly expense I suppose, as for this recording I had to get all the original oversized manuscripts of Schurmann’s orchestrations transcribed onto the Sibelius notation programme… which took a great deal of time and money. Then of course the orchestra is rather huge, numbering 100 musicians including 11 percussionists, 3 ondes Martenots, 2 grand pianos, 2 harps, 5 clarinets and an enlarged string section. Plus maybe my attempt with Silva put other companies off any recording… for although not a recording with which I was too happy it did sell very well for Silva. I was surprised that Maurice never really wanted to attempt a re-recording as certainly I was once approached by Robert Townson at Varese about providing them with the original manuscripts as they were considering a re-recording in Scotland. Also Maurice had a relationship with Milan Disques… so I was surprised that Maurice didn’t want to record the score with them. But I am glad to say that with the improvement of the Prague orchestra over the past few years and the sound that engineer Jan Holzner gets at Smecky Music Studios, I feel the wait has been worthwhile?

You mentioned the debate over the original Gerard Schumann orchestrations for LAWRENCE. Do you believe that Maurice Jarre has been unfairly criticized or that this orchestrator perhaps gets more credit than he deserves?

Yes, I do believe that from some rather vocal sources there has been the most unfair criticism. I do not want to particulary re-open that debate except to quote from one of Maurice’s other orchestrators: "You'll be happy to see Maurice's original sketches at USC soon. Maurice wrote all of LAWRENCE, which is in his handwriting. Same with ZHIVAGO. I think that the original orchestrator maybe made a bit of a stretch to claim otherwise! The sketches say it all." As I say in my sleeve notes for LAWRENCE:

Over the years there has been much debate in the film music community over the role in general of orchestrators and what their influence might be on the final scoring of any movie. There has also been more specific (and often unduly heated) debate over the partnership on LAWRENCE of Maurice Jarre and Gerard Schurmann. It is well documented that they did not see eye to eye! I will leave it to other more qualified persons to debate this further... if they wish. All I can add is that Gerard Schurmann’s orchestrations are vivid, challenging and imaginative, whilst Maurice Jarre’s thematic material is truly inspired; and, as CD 2 will show, this melodic inspiration continued for the next 40 years of his career in film music.

My final thought on the matter is that around the same time Gerard Schurmann did the orchestrations for THE VIKINGS and EXODUS and yet doesn’t seem too concerned about his lack of credit for these two classic films?

In addition to being album producer, you have been a conductor of the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. When you decide to conduct is it a personal choice because of some favorite music?

I try to conduct as little as possible and leave that to those much better at it. Plus you have much more control over both performance and recorded sound by producing… especially if to click… as when conducting you are concentrating on (and being distracted by) the click and often you can only hear the sections of the orchestra closest to you so that you have absolutely no sense of orchestral balance. I often to say to young composers who I contract orchestras for “Don’t bother conducting, unless you are really good at it, stay in the booth and produce”!

You have made such good choices for Tadlow CD releases, including epic soundtracks like EL CID and EXODUS. How do you obtain the necessary funds to complete and distribute such elaborate recordings?

I have been lucky that over the past few years the contracting and producing side of my business has been successful and that has funded the recording side. At the end of the day not one Tadlow Music release has recouped its costs. I knew that would be the case when I started it... but fortunately my main business helps to offset the losses of my "hobby"! But the signs have been there for the last two years that sales of CDs are actually falling and this is not being offset by enough revenue from downloads etc.! The only way some of these releases might earn extra revenue to help pay for them is by licensing out tracks for other usages, like commercials etc. I feel very lucky that with LAWRENCE and the next release, I have now recorded every one of my own personal choices. (all of which have been critically acclaimed... I am glad to say) So I need not record any other titles. But it would be nice to go on if the only reason was the preservation of film music: both the manuscripts and the audio recordings. For without this a great deal of music will be "lost" to future generations. It is just a shame that the very people who do make revenue from these copyrights... the music publishers... have never helped it this restoration of "their" music!!!

Of all your many previous releases on Silva Screen and Tadlow, can you name a few that were especially memorable or problematic?

I much prefer doing single composer scores or collections as compilations of different composers are much more difficult to record because stylistically each track is different and it takes a while for the orchestra, the conductor, the engineer and me to adjust to each new track. Among my favourite albums to record have been the John Barry ones like THE LION IN WINTER, THE LAST VALLEY, ROBIN AND MARIAN, WALKABOUT, RAISE THE TITANIC because at the end of the day (and I am not trying to be derogatory here) John’s music is very simplistic and formulaic, so everything is relatively easy to record and perform… it is more a case of getting the right “feel”, or waiting for the right “take” which can either be take 1 or take 5… who knows?

I also loved researching and recording the 2 albums I did of music by Jerome Moross: VALLEY OF GWANGI and THE CARDINAL. Plus I had great fun… and recording should always be fun… recording THE GODFATHER TRILOGY and THE PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN TRILOGY. And of course all of the Tadlow CD’s have been memorable because each album usually takes up a year of my life from beginning the research, trying to track down scores, to the score reconstruction process, and then to the actual sessions followed by intensive mixing, editing and mastering, and then finally to the preparing the artwork. I am totally involved with each and every process of the recording.

Problematic? Well most recordings have some problems to overcome… usually budgetary because there really is never enough time or money to record things as perfectly as I would like. I am certainly rather ashamed of some of the earlier productions I did in Prague and wish that I had spent a wee bit more time on rehearsals as in the early 1990’s the orchestra, while being good, were not up to the standard of London. One of the main problems with Prague in the 90's were the really awful recordings Thomas Karban did for Edel which were then licensed to Silva. Thomas just did not allow any time for the orchestra to rehearse... and expected a good performance after just one take, plus he swamped the orchestra in artificial reverb... so even the LSO would sound rather sloppy with no rehearsal. However, I also did my own fair share of poor productions for Silva (and other labels) in the 90's... mostly under pressure of tight budgets and little or no rehearsal. But also remember that the very first album I recorded in Prague on February 6th,1989 was FELLINI / ROTA... which still stands up today as a pretty good effort... as well as other albums of this time.

Also in that period the orchestra were totally new to this style of music and recording... when I first went to Prague they hadn't even heard of JAMES BOND... let alone the music for the films!!! Now they are among the best in the world... being the orchestra of choice for many British and American composers for their new scores. As well as currently recording more film music and classical/crossover albums than any other orchestra. One of the latest scores we recorded was THE EXPENDABLES for Brian Tyler. A pretty dramatic improvement in just 15 years!!! (Mind you I had to be rather ruthless in getting the core of musicians that I wanted... and I had to replace a few fine but not brilliant musicians, which is always a tough thing to do).

What recording projects are you working on now or considering for the future?

Just finished recording one of my all-time favourite scores… for another label… but I have been sworn to secrecy until the “official announcement” is ready… sorry. After that I am working on another Tiomkin score fortunately not as long as THE ALAMO. Plus I still have hopes of recording the complete QUO VADIS but there have been certain unexpected obstacles to this, but these are being surmounted with the help of EMI Music, the publishers. And I also intend recording an album of extended suites from Western Film Scores by Maurice Jarre, including VILLA RIDES, EL CONDOR, THE PROFESSIONALS etc.

Thank you, Mr. Fitzpatrick, for taking the time for this interview.