An interview with Albert Glasser

Albert Glasser: My Life in Film Music in 1700 words

From an interview by Randall D. Larson, December 6, 1981

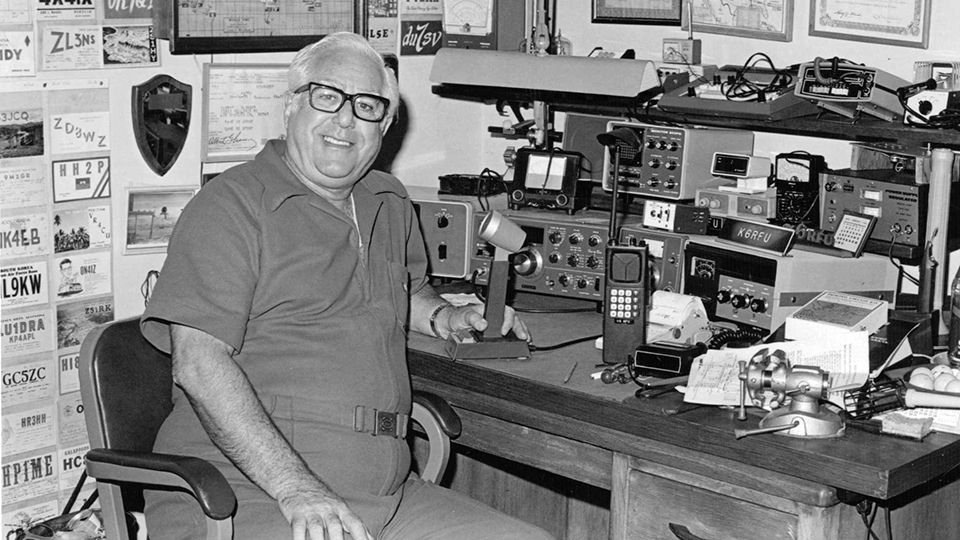

Albert Glasser seated at his ham radio equipment in BelAir, California

When did your interest in music begin?

I would say roughly when I was ten or eleven years old. I started taking piano lessons, but I didn’t have the patience to practice like I should, so I turned off of piano and turned to the flute. I became a good flautist. I played in football bands — got to see the football games free! — but it got me started, and I picked it up in a hurry. I became an usher at the Philharmonic Symphony, Hollywood Bowl, and very rapidly became wild about music. I fell in love with Richard Wagner, Johann Strauss and Richard Strauss, and it just developed and grew from there on.

What brought you into composing music for movies?

That came after I got through with my scholarship at USC, in 1934. I won the Alchin Chair Foundation Scholarship for composition and orchestration, and went to USC for six or eight months, but I didn’t learn too much of importance there. When I got through, the question was: well, now I’m a good composer and a good conductor, for a young man, but how do I make a living? This was in depression times, ’34, ’35… and everybody said “Look, a guy like you should go into the picture world, the Hollywood studios!” I thought that was a good idea, and I tried to break in.

I made a list of the various studios and their musical directors, and tried to contact each one individually on telephone. I called Leo Forbstein at Warner Bros and spoke to his secretary. I said “I’d like to speak to Mr. Forbstein.” She said “About what?” “Oh, I’m a young composer.” “Oh, I’m sorry, but he’s awfully busy right now,” which I figured. To circumvent that and find a way to get into the studios, I went to all the studios one day and waiting until the big shots came out. I asked a cop at the gates if Mr. Forbstein had come out yet. He said, “No, but he had a brand new Packard he just bought, with a new chauffeur. Gorgeous car. He leaves around five o’clock.” So I waited till five o’clock and he came out, him and his new car, and I wrote down the license plate. Went down the following morning to the license bureau downtown, traced his address, and figure out the best way possible to see him would be on a Sunday morning. So the following Sunday morning I went out to his house with a bunch of my music — my violin concertos, my string quartets, all that kind of junk I’d been working my brains out on. I rang his doorbell, and luckily he answered the door himself, in a bathrobe, and he said, “What do you want, young man?” I told him, and he said, “Come in, I’m having breakfast.” I went into his kitchen, was given a cup of coffee, and I showed him my work. He looked at it and said, “You have beautiful handwriting. You ought to be a copyist.” I said, “What’s that?” “Well, they copy out the parts for the orchestra. You get paid 50 cents a page.”

From that start I became part of the copying staff at Warner Bros. in the music library. At that point in time, Erich Korngold was scoring A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM and from there we went to CAPTAIN BLOOD, and I copied out a lot of that. I began to see what’s happening, how things were done. As one fast example, I would observe Max Steiner conducting one of his scores on stage, from a lot of things which I had copied off myself, and I’d see how he’d do it. When the orchestra would leave, I’d pick up the music from the stage, take I back to the library, put it on the shelves, catalog them, and when the copying staff would leave at 6:00 I would chase around the block, come back, and pick up some of Steiner’s sketches that I’d seen conducted that very afternoon. I’d take the sketches home, quietly, secretly, and analyze them; sitting up half the night analyzing what Steiner did. How did he catch that chord when Erroll Flynn shot the gun off, this marvelous effect, how did it work? I’d look at the sketch, “Oh, I see what he did here! The brass had this while the violins played that English horn played this while the cello played that. Excellent, beautiful work! I memorized a lot of his tricks, effects, and things. That’s a rough picture of how I got into the studios.

How did your first film scoring assignment come about?

Very simple. I was working as an orchestrator at MGM, on the staff during World War II. The man I was orchestrating for, Nathaniel Shilkret, used to say “Look young fella, you have a marvelous gift for writing. What the hell’s the matter with you? Stop orchestrating! You’re making a lot of money, but he real money is in composition. So get yourself into ASCAP and score movies. Get your name intro ASCAP and it’ll pay for the rest of your life!” So I went along to various studios, but I had no credits. Wherever I went they said, “We know you’re good, young man, you’re terrific, great orchestrations, fine conductor, but you have no credits. We can’t sign you.” So finally I went to the private individual who controlled some of the small time composers in town (at the time MCA controlled everything. They wouldn’t even touch me with a ten-foot pile because as nobody). I went to this guy, David Chudnow, and said “Look, I need credits!” He said, “Alright, I’ll tell you what. I’ve got a picture coming up, a mall one, a little stinker. I’ll give you $250 if you compose and orchestrate and copy and conduct; do the whole thing for $250.”

I said, “Oh my God, that’s like doing it for nothing.” He said “Sorry. Take it or leave it.” I said I’d take it. It wasn’t a question of the money, I wanted the credits. So he gave me the first little picture I composed, which was THE MONSTER MAKER (1944). Good little score, and at least I saw my name on the credits for the first time, up on the screen. Once I got my hand on that, knocking on the studio doors, saying “Hey, I’ve got a credit! I’ve got a credit!” little by little things began to happen. Columbia called up, “We saw your little picture, can you do a full score for us?” “Be happy to!” Wherever I went, it picked up.

The next picture Chudnow gave me to score, he said, “Well, I’ll give you $50 more,” and little by little he began increasing my salary. But luckily one of the guys I worked for at first, for very little, was a gentleman named Phillip Krasne, and he gave me a little film called CISCO KID to do, an unknown series that was just getting started. Krasne called up about six months later and said, “Hey, we got another little picture, a little jungle thing. Want to do it?” I said sure, and I came over to his office and he said, “What’d you get on the last show, that little CISCO thing?” I know where this was going, so I said “About $350.” He said, “What?!” and almost swallowed his cigar. “I gave Chudnow three thousand bucks!” I said, “Well, Chudnow kept it, he gave me $350.” He got on the telephone, called Chudnow, and said “You lousy crook! Don’t you ever come around here anymore!” So from there on I was in like Flynn with Krasne. The CISCO KID went into a series and developed into a big thing, and eventually came onto television and that opened up the doors.

What prompted your retirement from film scoring afterwards?

There are several good reasons for that. Number one, rock and roll was coming in so heavy in the middle ‘60s. Wherever you went, they wanted a rock score or an electric score. On my last film, CONFESSIONS OF AN OPIUM EATER (1962), they didn’t want any instruments at all, they just wanted synthesizers, so I had about five or six electronic things. It didn’t come out bad, as far as I was concerned. But with that, you’d walk into a studio, talk to a young producer (I say young because I was getting older) who’d say “Can you give me a rock score, real cheap?” “Nope,” I said. I tried but no go. But the whole area was changing. All the old B movies were finished and gone forever, television was so strong and so heavy, and most of the features were just big, colossal things. Most of the production crews that I’d worked for over the years were getting out of the business. They couldn’t make any more money. All of the sudden all my sources of income were drying up. The only things that were left were movies with rock and roll music, and television series, which were all handled through MCA, of which I was not a member, and I was off in the middle somewhere. So I retired for about two years, until I got tired of playing golf and accidentally fell into piano tuning. I started to take some lessons in piano tuning and got hooked on it. It was right down my line — I had a great ear for music to begin with, and I’m also mechanical. So that’s become a fulltime thing and I love it.

Do you ever get the urge to write again?

Oh, yes. The urge is always there. Music never stops, 24 hours a day it’s always roaring through your head. And the desire to write? Yes, but the question is: what for? I wrote so much music. The ability to write, it always was there, and always will be, but unless there’s a reason for it, you tell me why I should, and maybe I might!

Remembering Albert Glasser, the Best Piano Tuner in L.A.

January 25, 1916 (Chicago) – May 4, 1998 (age 82, Los Angeles)