Alex North’s 2001 and Beyond

Alex North’s 2001 and Beyond by Kirk Henderson

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.13 / No.49 / 1994

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven and Kirk Henderson

In 1983 I was working as an art director for the studio which did the special effects for THE RIGHT STUFF. Though I was not personally involved in the effects, my knowledge of film music was well known around the studio and director Phil Kaufman, who was frequently coming in for meetings, asked me who I would recommend to do the score. Without hesitation I said, “Alex North! You couldn’t find anyone better!” A few days later he asked me for another suggestion, telling me Alex North wasn’t available and adding that he had also heard that North was difficult to work with. I had no idea what the Hollywood of 1983 thought of Alex North, so I could not disclaim Kaufman’s statement (though I found it hard to believe). Even so, I suggested to him it would be worth any amount of difficulty for a North score. Kaufman, however, had made up his mind – he wanted other suggestions. Well, without Alex North, who was left? Jerry Goldsmith was the only name I could think of, but I wasn’t surprised to learn that Goldsmith was booked for the next year.

Ultimately, the choice came down to John Barry, not because I recommended him, but because Kaufman had heard some compilation tapes I had made of Barry’s work which included his more introspective side such as the delicate THE WISPERERS. In an interview in Soundtrack! No.43, composer Bill Conti – who ended up replacing Barry for THE RIGHT STUFF – said Kaufman told him he wanted something small and personal, and so the intimate sound of John Barry must have been just what Kaufman was looking for. Kaufman borrowed the Barry tapes from me. (I still haven’t gotten them back). Though I told him John Barry was a fine composer, I said I didn’t think he was the proper choice for THE RIGHT STUFF. Nevertheless, Barry was hired. The paperback tie-ins of Tom Wolfe’s novel even have Barry’s name on its film promo page. But after Barry played what he had written for Kaufman on piano, he was replaced by Bill Conti. It was later explained to me that Kaufman didn’t like the direction Barry was taking and also had personal differences with the composer. In any case, Conti came into a situation very similar to what Alex North must have found himself in with Stanley Kubrick and 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY.

Like many directors Kaufman had temp tracks in place for THE RIGHT STUFF. As Kubrick had done with 2001, Kaufman had grown accustomed to some of his temp tracks and Conti’s music even ended up incorporating some of them. Viewing the finished film, however, it’s clear Conti’s score fits the heroics of THE RIGHT STUFF, even if Holst’s The Planets is still there, and even if Kaufman was not happy with the results. The bold main theme, though conventional, is certainly memorable, and can even claim the distinction of being heard today in marching bands at football games around the country. The score won an Oscar, but I still can’t help wondering, every time I hear Conti’s heroic theme – what would Alex North have done had he been given the chance?

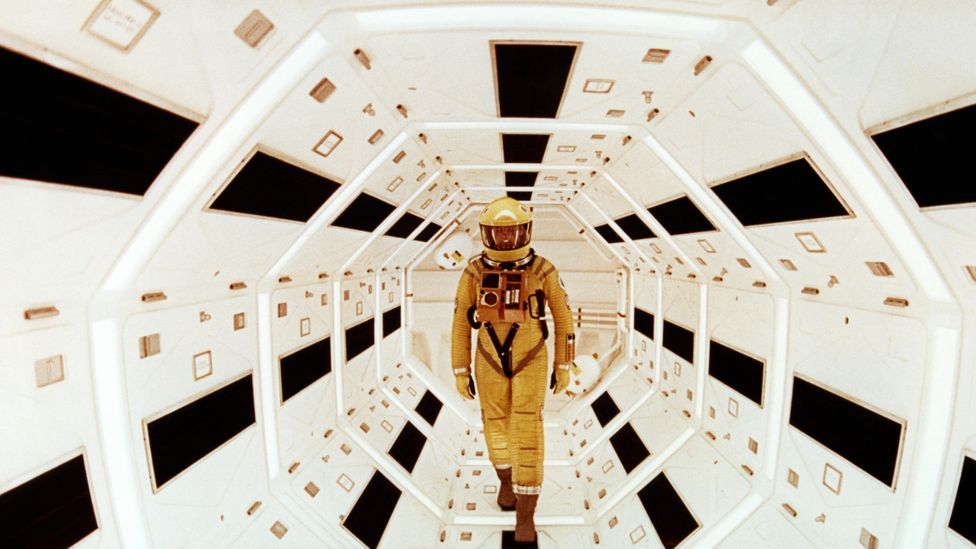

With Varèse Sarabande’s release of Alex North’s music for 2001, it’s clear what direction he might have taken for THE RIGHT STUFF. It’s very possible we would have had another epic masterpiece. As the cover of the 2001 CD suggests, Alex North’s unused scored had become legendary, but few things live up to their legend.

In some ways, 2001 and THE RIGHT STUFF had similar musical requirements. They needed something to give the viewer a sense of passing beyond boundaries, to represent the majesty of achievement, and complement the concept of men in space. Had he done THE RIGHT STUFF, North would most certainly have created something powerful and grand as he demonstrated many times before in his epic scores for SPARTACUS, CLEOPATRA and THE AGONY AND THE ECSTASY. This would have pleased Kaufman, who was looking for an intimate score, but considering some of the bravura in 2001 – such as its ‘Main Title’ and ‘Entr’acte’ – North would certainly have been able to fuel the airborne sequences for THE RIGHT STUFF with enough glory to please the producers.

Had North’s score to 2001 been used, Kubrick’s film would have been starker in some places, more lyrical in others. The brutal desolation of the Dawn of Man most certainly would have been more savage with North’s harsh, clipped percussion and high pitched woodwinds. On the other hand, the wonderful ‘question and answer’ woodwinds North had planned on accompanying Dr. Floyd’s call to Earth and his amusing conversation with his daughter on Bell’s Picturephone – a sequence without music as it stands now – would have had a much more magical feel. Where the low register instruments ‘breathe’ in and out as a ‘question’, they are ‘answered’ in kind by similar musical phrases in the high register after a short pause. The repetition of this contributes a random, almost floating sensation and a sense of lyricism to the drifting moon we see outside the window of the space station’s phone booth.

North’s 2001 is anything but conventional, yet it has the markings of the period from which it came. Strangely, the strident and modernistic orchestrations used predominantly for the early ape sequences remind one of Jerry Goldsmith’s savage rattIings for PLANET OF THE APES, released a year earlier in 1967. Both scores achieved an abrasive futuristic sound with the use of traditional orchestra, augmented with a few unconventional instruments.

To see how well 2001 fits within its own period, just consider another fine score written 9 years later, also using a conventional orchestra for a modernistic sound: CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND. For one, John Williams did not use percussion the same way North and Goldsmith used it in the late 60’s. Williams’ percussion is frequently recessed within the brass and strings, less dissonant as a result. But North and Goldsmith allowed their percussion forward, sometimes in stark isolation. This is certainly true in ‘Eat Meat and the Kill’ from 2001, where the brass and percussion more than overlap, and in the ‘Main Title’ to PLANET OF THE APES in which the percussion and woodwinds interplay over a forward moving rhythm, often isolated from each other. Secondly, by the finale of CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, Williams’ string section tries to elicit our wonder and emotion very directly with a full orchestral rendition of the five note ‘conversation’ theme. This sort of sweeping “feel good” sound was almost unheard of in the science fiction scores of the late 60’s, where the trend eventually led to the cold electronics of Gil Mellé’s THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN a few years later. North’s 2001 and Goldsmith’s APES certainly pointed in that direction.

By comparison, THE RIGHT STUFF, an 80’s score, though likeable, is quite conventional by comparison to what North achieved with 2001. At its least effective, Conti’s score recalls John Philip Sousa; at its best, there are scenes with the strength of Aaron Copland. But its patriotic march is the only real standout piece in the whole score. The only other memorable bit is the ‘Mars’ excerpt from The Planets, rewritten by Conti, but so closely resembling Holst as to be the same thing. It is still quite effective. Its brooding orchestral build as John Glen sits in his capsule, preparing to be blasted off the planet, keeps the scene suitably tense. However, North’s ‘Moon Rocket Bus’ for 2001, written to accompany a space shuttle crossing the moon landscape, has a similar pensive quality to it.

Almost expectedly, it was THE RIGHT STUFF’s raw nationalism that annoyed some critics when the film was released. Conti’s traditional approach in scoring only added more steam to the film’s already full-throttle heroics. But The Planets did not ruffle the critics’ sensibilities like Kubrick’s use of Strauss’s The Blue Danube did in 2001. Some loved the juxtaposition of space craft floating across the screen to the accompaniment of a graceful waltz. Others thought the association to old Europe got in the way of a brilliant visual tour de force.

Alex North’s complex but delicate waltz for the same sequence, and his use of alternating woodwinds and strings would have been a vast departure from Strauss. Many of us will recognize this music, having heard it before in North’s own DRAGONSLAYER. But in that film, it was never given a showcase like it would have gotten in 2001 and the piece is more developed and extended for the space docking sequence. In DRAGONSLAYER this piece accompanied the airborne dragon, and inasmuch as the creature decimates a whole village, the music is somewhat incongruous.

Stanley Kubrick’s use of Also Sprach Zarathustra and The Blue Danube has been copied and satirized so much since the release of 2001, it’s difficult to appreciate their original effectiveness. In fact, the use of Zarathustra for the grand image of the Earth, sun and moon in alignment made such all impact on the public, it has been reused ad nauseam (even appearing in salad dressing commercials!) and has become a tool of parody. I do not believe North’s cue for the celestial opening of 2001 would have become the object of parody like Zarathustra: North’s piece is more sophisticated. Its greatness lies in its ability to provide a rising series of orchestral climaxes, each outdoing the previous, even after the listener has thought the pinnacle had been reached.

One of the finest pieces on North’s 2001 is ‘Moon Rocket Bus’, which includes a siren-like female vocal, interweaving endlessly as the bus floats across the barren moonscape. This is the most haunting cue on the disc. The vocal adds an emptiness to the whole affair, accented by chimes and glockenspiel, while a rhythm of strings and rising brass races underneath. The tempo slows momentarily, and an organ pulls us inside the moon bus. For this short conversation between Floyd and the other two men on their way to the monolith excavation site, the vocal recedes and a plaintive mood is created by French horn.

Though impressive, the only piece I question on the disc is ‘Entr’acte’, which seems more suited for the documentary North finally placed it in – AFRICA. The mid-way break into the classic jazz-related harmonies seems inappropriate for the tone of what we were about to see in the second act of 2001. An introduction to the desolation of the spaceship Discovery in the empty reaches of space needed something colder. Perhaps this was also what Kaufman objected to with John Barry’s approach to THE RIGHT STUFF. Barry’s later scores have a serene, sometimes morose quality as a result of his dependence upon lush, extended strings. This is not to say strings would have been wrong for THE RIGHT STUFF, particularly since Bill Conti did use them to good effect North’s strings however are in sharp contrast to anything by Barry or Conti; North tended to use them sparingly, playing off the woodwinds in short bursts, or to add rhythmic textures.

I don’t know if 2001 would have been better if Kubrick had used North’s score. It would have been a different film, perhaps just as good, maybe better, but in all honesty the film as it stands now is still a monumental achievement, The Blue Danube and all. 2001 with North’s score may have been perceived as PLANET OFTHE APES was upon first release: A landmark score, the accomplishment of which could only be fully appreciated by film music aficionados. On the other hand, the Kubrick selections became internationally famous. I’m sure it was an introduction to serious music for many who otherwise would never have heard of Richard Strauss or Gyorgi Ligeti. In fact, Khachaturian’s adagio from The Gayanee Ballet Suite worked so well in the spaceship Discovery sequence, it managed to influence others years later. Take note of James Homer’s music for the opening of James Cameron’s ALIENS.

What is clear is that had Alex North also scored THE RIGHT STUFF, there would have been an improvement to the film. I don’t mean to belittle Bill Conti’s work, because it did fit, but the film could have used something more. Chuck Yeager breaking the sound barrier needed the grandeur of a ‘Main Title’ to 2001; Yeager’s spin/fall from the X-15 and his subsequent survival relatively unscathed could have used the clashing brilliance of a DRAGONSLAYER; the anguish of the astronauts’ wives could have benefited from the introspection of an UNDER THE VOLCANO or a SOUND AND THE FURY. All North scores. All brilliant.