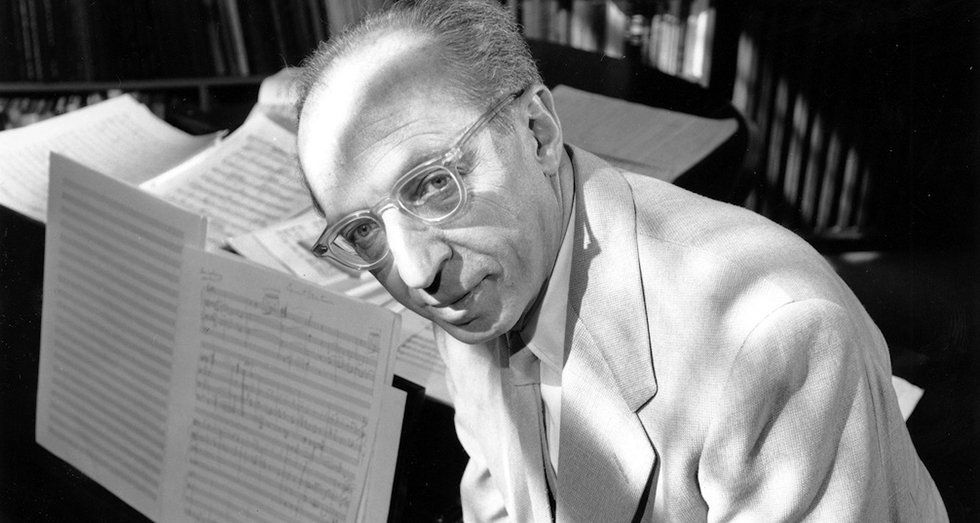

Aaron Copland talks about Film Music

An Interview with Aaron Copland by Roger Hall

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.19/No.75, 2000

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven and Roger Hall

Between 1939 and 1949, the distinguished American composer Aaron Copland (1900-1990) composed five major film scores: OF MICE AND MEN, OUR TOWN, THE NORTH STAR, THE RED PONY, and THE HEIRESS. He also composed scores for two documentaries: THE CITY (New York World’s Fair, 1939) and THE CUMMINGTON STORY in 1943. His last film score was for the 1961 drama, SOMETHING WILD, not to be confused with the later 1986 film.

Interviewed in the composer’s spacious home in Cortlandt Manor, New York on July 21, 1980, Copland spoke candidly to author Roger Hall about his days in Hollywood during the 1940s and about his film scores. “He was most cordial to me and full of laughter and high spirits, even at nearly 80 years old,” recalled Roger. “I was very pleased to finally meet my idol – the man I consider to be the greatest American composer of the 20th century. It was an afternoon I’ll never forget!”

In your book, “Our New Music,” you said that you worked at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio in Hollywood and you did a lot of your composing at night.

Yeah, at night everyone went home about 5 or 6 o’clock. So the studio grounds were like a walled city. You couldn’t get in or out without passing a guard. The streets were all darkly lit and it had kind of a medieval feeling to it. So I liked to work at night. The working conditions were perfect as far as I was concerned. I could work until midnight or even all night if I liked. Since I always tended to be a night worker anyhow when I was composing, it was just an ideal setup for me.

How did you compose your film scores at that time?

It was great fun to first see the film – it has no music of course. Then decide where the music is going to be used, because it’s not continuous from beginning to end. Next write the music, orchestrate it, record it, and add it to the same picture which was silent. And then with the turn of a knob you can both hear the music to the scene, turn the music off and see the scene without any music, and turn it on again. I’d like to do that with a movie audience sometime. They don’t realize the extent to which music is influencing their emotions. And that maybe would give them a better idea of the purpose that serves the needs of the film by using effective musical sounds.

You wrote an article for the New York Times back in 1949 that said the moviegoers should be taking off their earmuffs. That was a marvelous way of calling attention to how few people notice the music in a film.

Well, it works on them without them even knowing it.

I also read that you met Groucho Marx at a classical music concert and you told him not to tell Samuel Goldwyn. You said you had a split personality. And Groucho said…

That’s okay as long as you split it with Sam Goldwyn! (laughter)

Did you feel that the concert works you were working on were separate from the film scores you were writing?

Well, they serve two different purposes. When you’re writing music for a film, you know that it’s not going to be listened to like concert music. People should be absorbed in the story of the film. Very often they don’t even know that music is going on, though it affects their emotions. The music mustn’t get in the way. But on the other hand, it must count for something. It’s quite expensive to add music to a film. It would be a shame if nobody paid attention to it (laughter). The producers would have thrown their money out the window.

You put together a concert suite, ‘Music for Movies’. Is that like other suites you did, such as from your ballet score, Appalachian Spring?

Yes, it’s very similar.

Did your friends ever mention film music?

Very often I’d go to a movie in the old days with some friend and ask – “well, what did you think of the music”? He’d reply, “what music? Was there music going on”? They think that’s a compliment to the director because then the music didn’t get in their way.

Some past film composers believed that you shouldn’t be too aware of the music.

I believe too that it shouldn’t take up so much of your attention that you stop thinking about the film. It’s a high art, I think, to write a really effective film score that doesn’t get in the way and serves a fully emotional purpose.

Some great classical composers of this century, such as Prokofiev and Vaughan Williams, have written for films. Even so, there still seem to be some who think that film music is second rate and not the same as concert music.

Well, a lot of it was done by what you might say were movie composer “hacks.” In other words, composers who had to write whatever was thrown at them. I had the luxury of not having to live in Hollywood. Once you were on the staff at a studio then you didn’t have any choice.

Then you were never actually on the staff at any studio?

That’s right. I was brought in especially for a film. And then I was very careful to get the hell out of there once I was finished. It’s very tempting to stay there. The salaries were very good – better than you could get in any other field of music writing.

Besides writing scores for feature films, you also did some documentary film scores, such as THE CITY. How did that come about?

You really couldn’t get invited to Hollywood if you’d never done any film music before. You could have been the greatest concert or operatic composer. They wouldn’t be impressed by it. They had to see what you did with films. So it was a stroke of good luck for me that a group of architects decided to ask me to put that short film to music. Then I had done music for a film and that induced the invitation to write a full film score.

What about working with orchestrators in Hollywood?

Oh, I did my own orchestrations.

Some film composers still use orchestrators.

Well, they have some expert orchestrators out there.

One orchestrator who comes to mind from the 1940s was Hugo Friedhofer.

Yes, he was an expert orchestrator.

Did you know any of the film composers who were around in the 1940s, such as Bernard Herrmann?

Yes, I knew Benny. I knew him before he went out to Hollywood.

There’s one of your film scores that never received a soundtrack recording: THE HEIRESS. Were there ever any plans to record that Academy Award winning score?

No. Some of the excerpts are on the short side and hard to work into concert suite form.

But you did do a suite from an earlier film, OUR TOWN.

Yes, that’s true. That was a nice film to work on because it lent itself to musical commentary.

Some people have said they hear American folk tunes in OUR TOWN. Did you use any?

Not that I can remember. That was so long ago. Some of the score was in the manner of folk material, so it may have been thought to be taken from folk music.

How about the movie audience? Do you think they should be more aware of film music and “take off those earmuffs”?

I’d love to be able to have audiences see a film with the music. Then see it a second time with the music turned off. And then see it a third time with the music turned on again. Then they’d get a much more specific idea of what the music does for a film. Otherwise they simply take it for granted. They don’t even know that music is going on, if they’re not very musical. Of course, people who are musical can’t avoid listening to it. If they’re not musically inclined, they can’t be bothered.