A Conversation with Maurice Jarre

A Conversation with Maurice Jarre by James Fitzpatrick

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.3 / No.12 / 1984 and Vol.4 /No.13 / 1985

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven and James Fitzpatrick

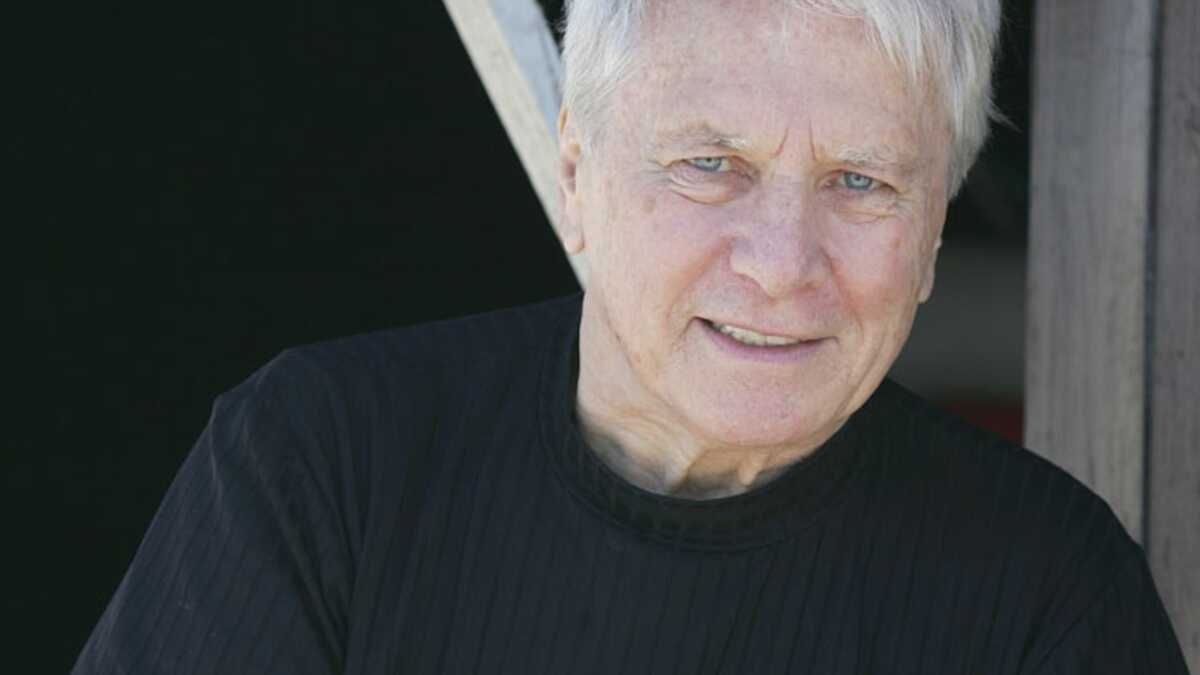

This interview with Maurice Jarre took place at his apartment in London on April 12th 1984, just after he had finished writing and recording the score for TOP SECRET. I had first met Jarre a few years earlier on the recording sessions for LION OF THE DESERT and had kept in touch over the years. He is now (mid-September 1984) starting to write the score for the new David Lean film, PASSAGE TO INDIA, and later this year will score the new Peter Weir picture WITNESS. Maurice Jarre is an extremely modest man, without ego, and is genuinely surprised and pleased when people take an interest in his music, or in film music in general. After thirty years of writing for film he is still very passionate about music, while being cynical about parts of the movie business, although resigned to the fact that he has very little control over his music once it has been recorded and left in the hands of the producer or director. He likes to produce his own soundtrack albums, after many unhappy experiences with different record producers on LPs like SHOUT AT THE DEVIL and NIGHT OF THE GENERALS and prefers to remix and edit into longer tracks or continuous pieces of music (as with CIRCLE OF DECEIT, THE TIN DRUM and LION OF THE DESERT).

At which stage do you prefer being brought into the production of a film?

As early as possible, because if you have read the script, even if the director and producer make changes, there is still the basic idea. You have the tine to think about the film, and if it is a period piece or a picture involving ethnic music there is plenty of time to do your own research.

Does that often happen?

Well, when you work with a director more than once, when he prepares his next film he can at least give you the script even if no contracts are signed, and so you know that he wants you. But it is true it is quite rare that this happens; I am bemused especially if it is a ‘serious’ director who has thought carefully about the music he wants in a film, yet he can give the composer only three weeks, although the director night have been involved with the picture for 2 years. The music is always left right to the last minute!

So with PASSAGE TO INDIA you have been brought in at a very early stage?

Yes, but with LAWRENCE OF ARABIA it was a different story – really crazy! I don’t want to bore you with the story, but I barely survived this experience from the physical point of view, having to do everything in six weeks. I was only sleeping about two or three hours a night. I don’t want to have this kind of experience too often.

Would you say that film composers are treated any better by producers or directors now as they were thirty or forty years ago?

That is a very interesting question. I don’t want to be pessimistic, but I think the situation will get worse and worse. Many directors have a music complex and find it hard to communicate with the composer. I prefer directors who tell me things like “It should feel very romantic,” or “Very soft sound,” that is easier to understand, rather than directors who make comparisons with classical pieces, so they can go too far and request things like an oboe solo when they really mean a clarinet or bassoon solo. Some directors are very insecure about music and don’t really know what they want, so we can mess about for weeks trying different instruments, and finally it ends up with the director not trusting the composer. The composer has a certain talent and training and should always be treated as a trusted collaborator. The main problem is that a director can explain better technically to the cameraman or art director than to the composer – the music is an abstraction for them.

I was lucky to meet Dimitri Tiomkin and had long talks with him. In his day they had problems with the studio bosses like Jack Warner or Louis B. Mayer, they were dictators, absolute tyrants who could stop composers from working in Hollywood for the rest of their lives. During the 30’s and 40’s the big studios like Warners had five to ten composers in residence, who knew exactly what they were doing. These days, the problem is that any rock singer can have a hit song so the director says. “Let’s use this guy, he’s really great.” So they ask him to write a full score and what happens? The producers have to provide a good arranger, orchestrator, conductor and music editor, because this guy knows nothing and it finally becomes a totally dishonest work.

It sounds very much like the type of thing Michael Winner did for THE WICKED LADY, where he used the keyboard player from Genesis. Tony Banks, as well as Christopher Palmer to orchestrate, and Stanley Black to conduct.

Exactly. It is totally immoral. How often do we see film credits with music by so – and – so, when in fact he has written three notes and had help from so many other people to finish a complete score? I think that serious directors like David Lean or Volker Schlöndorff would not do this.

In a book on John Frankenheimer he was quoted as saying that he was totally at sea with composers and did not know how to communicate with them, until he worked with you on THE TRAIN.

I must say that even during filming of THE TRAIN he was helped very much by Burt Lancaster. He was very reluctant to even tell me what his feelings were about a scene, in fact I practically spotted the film with Burt Lancaster.

One of my favorite scores is for Frankenheimer’s THE FIXER, scored for solo violin and percussion.

THE FIXER with John was very interesting, because he liked the idea of the violin solo but didn’t really take good care of the post-production of this film because he was already involved with another picture. It’s a pity, because it should have been much better, especially the final dubbing and mixing. It was a very unusual idea to ask for only one violin to be the main score in Hollywood at that time. We were destroyed by the Hollywood critics, but I still think that it was a very interesting film. I remember the movie MOURIR A MADRID had the same kind of concept for the music, basically scored for one guitar. It is more difficult to write this type of score because you have to have a strong theme which also has to be interesting, so you are limited with the color of orchestration. It can be very effective, and I love this kind of thing.

So for PASSAGE TO INDIA you are going to score it for solo sitar?

I think that is exactly what David Lean does not want. I don’t think he is too keen about Indian music. This is an example of where I received the script before they started shooting and I was thrilled by David’s script, I think it is the best screenplay for his films. When you read the script you almost see the aura of the picture, everything is there in the script. I was thinking about it the other day and it is such a story that could only happen in India at that period in history, so I think we should have some Indian flavor, at least from the instrumentation side, although the sitar has been so exploited.

Does David Lean ever fit a temporary music track to the film, or does he let you see it absolutely ‘cold’?

No, usually he does not use a temporary track, although with the source music he records it for the actual shooting, as in LAWRENCE OF ARABIA: the military band was really playing and not faking – maybe not played very well, so that we re-record that music for the final score. Thinking about your question, David did use a temp track for DOCTOR ZHIVAGO. He fell in love with a supposedly old Russian folk song, a very nice piece of music. When I viewed the rushes, he said that he wanted this theme to be incorporated into the score. However, when MGM tried to clarify the copyright situation, it turned out not to be a traditional folk tune, but an original piece of music for which MGM could not get worldwide clearance; so they did not want the theme used.

When I heard about this decision, I had to start to write something completely new with only a few weeks to go to the recording sessions. Up until then, I had been relaxed because I knew that I was going to use this folk song as the main theme. So when writing a new theme, subconsciously or not, I tried to go around this melody that I had heard so many times before to get the same kind of feel and phrasing. Every time I presented a new theme to David, he rejected it and said that I could do better. I wrote four different themes in this time, but none of them was quite right. By this stage I was not only getting depressed, but also panicking because time was running out. Then, one Friday, David told me to stop work, to stop thinking about the film or the music and go away for the weekend to the beach or mountains, to clear my brain and start afresh on Monday. So I did this, which was very hard because of the pressure and with the days running out. Anyway, Monday arrived and I realized that the stupidity was this temporary track. I should try to write something totally different, and I wrote a kind of waltz. After those 2 days of clearing the brain, in one hour on Monday morning I had found “Lara’s Theme“, which was the opposite of the original temp track.

What was it like working with Alfred Hitchcock on TOPAZ?

It was very interesting, with Hitchcock it was

power and not ego you had to deal with. Power is different, ego is very negative and destructive. Hitchcock was very open and didn’t give me many instructions; he left me alone, which in a way was quite frightening because of his reputation. I liked working with him, although I was slightly disappointed because I thought he would be very precise; I like precision, as this means fewer problems arise at the last minute. When people are not precise it means that they do not know what they really want.

Do you have any particular directors you enjoy working with?

I liked David Lean of course, plus Schlöndorff, a very interesting man. I really like these 3 directors on TOP SECRET, they are probably the youngest people I have worked with; they are very intelligent and passionate about movies and without any egos. It is incredible, how can three people direct a film without any fighting? They argue of course. I was a little uneasy at first having to work with three directors, in fact four as Jan Davison (the producer) is also very creative, so sometimes you have to deal with four different views, which is fascinating. I enjoyed the experience immensely. They are full of ideas and know exactly what they want.

Are there any types of films which you prefer scoring? Is it any easier to score a western for example?

Everything is difficult. I love change, I like variety. It is not a good idea to score too many of the same kind of film, science fiction films for example. Jerry Goldsmith at one time was doing too many S.F. films, and it’s even worse for John Williams. They always ask him to do the type of big orchestral score. This was fabulous for STAR WARS, but after that he has become very repetitious. The big problem in Hollywood is that they classify you too much. They would never ask John Williams to do TOP SECRET, or vice versa, they would not ask me to do a STAR WARS sequel, not that I would do it anyway. You are classified as a composer who can only score certain types of films like westerns, as in Elmer Bernstein’s case, or are only able to write songs or score epics. It is embedded in the minds of producers that you can only write certain types of music. After LAWRENCE OF ARABIA they thought I was only able to write desert music, then after ZHIVAGO I could only write snow music. Now I am very lucky to have the opportunity to try different film subjects. The last few pictures I have scored have varied from THE YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY to DREAMSCAPE, both with electronic scores, to FOR THOSE I LOVED and TOP SECRET with large orchestral scores.

Recent years has seen the growth of T.V. films, are there any added restrictions when scoring this type of film?

To tell you the truth I don’t like T.V., unless you have the chance to work with someone like Zeffirelli on JESUS OF NAZARETH. Generally in T.V. everything is too hurried, without caring about wrong notes, and with poor sound. I do have great hopes for cable television, in that it seems to be attracting some good, talented directors. Commercial T.V. is under too much pressure from the ratings. I wrote a T.V. score for a friend just before I came to Britain, SAMSON AND DELILAH, it was not a very good film but at least because I was working with a friend more time was given over to achieve better sound and music recording.

What was it like working with Zeffirelli?

It was fabulous. Zeffirelli is an artist. He has this Italian way to work, which is that time has no meaning; he is very careful and precise about what he wants. He is very knowledgeable about music, we can talk easily because he is able to tell you things like, “I would like to have the atmosphere of the first part of the second movement of Mahler’s 2nd Symphony.” He can give you an exact idea of what he wants. This is very rare.

Were you ever tempted with JESUS OF NAZARETH to write a Hollywood type epic score, with heavenly choirs as in BEN-HUR?

The answer is yes. I did talk with Franco Zeffirelli about having a choir, but he was afraid of having too much of a religious choir feeling, giving the music too much drama. I would like to write a score with a choir, I have many ideas about this but never have had the right opportunity. The problem is that there is never the time to try out new ideas. I don’t mean crazy experimentation like writing a score for two typewriters, but at least having the time to rehearse. On TOP SECRET we had a very tight schedule – one rehearsal, maybe an extra rehearsal for longer pieces and sometimes more than one take, but that was all.

What is it like working with actors who have become directors, as you have worked with Clint Eastwood on FIREFOX and Paul Newman on GAMMA RAYS?

I was a little afraid that Paul Newman might be a star with an inflated ego, but he was a charming man, a very good director, very professional, with a great eye for editing. It was a fabulous experience, I loved the film although it did not require much music. FIREFOX was a slightly different story. Clint is also a really charming man, absolutely adorable, the only thing is that he does not trust the music. There are some interesting things in the film, but it was not a very good picture. I like to have a basic concept for any score. The idea for FIREFOX, and Clint loved this idea, was to have the first part of the film (up until the plane is stolen) with an electronic score; then, when the plane is stolen, the music should stress the adventure aspect with a big, orchestral score. He loved this idea, but loved the sound effects even more, so most of the music was lost at the cutting stage.

So it is almost as if you were writing two separate scores for one film?

Exactly. The first part was very difficult. We did a lot of things with synthesizers and electronic machines. For instance, all the sounds of the helicopter at the start of the movie are all electronic and part of the score.

Are there any films that you have seen which you would liked to have scored or thought would be an interesting challenge?

There are many, of recent films I would like to have done GANDHI. I recently saw NEVER CRY WOLF and THE BLACK STALLION, two beautiful pictures. This type of film I would love to score, whether a film is commercial or not does not enter my thinking.

When we last met 3 years ago, you were recording LION OF THE DESERT, and at that time you were hoping to score the new Bounty film to be directed by David Lean as you had already read the script. Now everything has changed, with a different director and a Vangelis score.

I am happy in a way not to have done this picture, as it was a script written for David Lean: I would have considered it a betrayal of his friendship.

Are there any recent films that have been offered to you that you have turned down?

There were 2 films for TV, one was about Sadat, I was probably asked because of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA, and the other was PRINCESS DAISY. I was very tempted to do DAISY as I liked the director, Waris Hussein, and had worked with him on another telefilm COMING OUT OF THE ICE. That was a marvelous film which even the bad taste of the TV people could not destroy.

Have you ever been in the situation when you have been asked to score a film which has already been scored by another composer, but whose music has been rejected? For example, THE ONLY GAME IN TOWN had three composers – first Alex North, then Johnny Mandel – and finally yourself…

Usually when it is a situation like that I would say no. I don’t like being put in that kind of situation. Richard Lester asked me to do a very interesting film, ROBIN AND MARIAN. Michel Legrand had written the original score in the form of a concerto. I could not understand Lester not liking Michel Legrand’s score, as he had worked with him before and knew his style. Richard Lester was really nice, but I had to say no as I would only be given about two weeks in which to complete the score. I believe that if you hire a composer, you should be able to ask him to do anything, unless that composer is a real diva, a prima donna who will not let anyone touch or alter their music.

Have you ever had any of your scores rejected?

I’ve never had any rejected, apart from music for CHU AND THE PHILLY FLASH. I knew the director, David Lowell Rich, and had worked with him on ENOLA GAY. He asked me as a favor to write the score, as I thought the film was really awful; I said I would write some light background music. Anyway, after recording the music everyone was happy with the score. Then later on Alan Arkin and his wife (being co-producers) changed the score, as they had not been consulted about using my score; David Lowell had been fired and was threatening to sue, so Pete Rugolo wrote another score which was used in the theatrical release. Still, I presume that David must have won his case, because when shown on TV my score was reinstated. I had the same kind of problems in France in that if you are friends with the director and he makes a bad movie, it is very difficult to refuse to write the music because of that friendship. It happened even with John Frankenheimer when he made THE EXTRAORDINARY SEAMAN starring Faye Dunaway, Alan Alda, David Niven and Mickey Rooney – a very good cast, but a dreadful movie!

Have you composed any music for the concert hall since your ballet “Notre Dame de Paris” in 1965?

I wrote a little piano concerto for a friend in California when we toured Japan. It was a homage to Kurosawa. Again due to lack of time, this was the last concert hall piece I wrote. Fortunately I manage to keep very busy and if I have an odd week or two off, I am usually too exhausted (not from the actual composing, but more from the pressure of schedules) to write anything else. TOP SECRET was very tiring, for many reasons: because there were a lot of notes, much pressure and 3 directors to keep happy. After finishing a score, you suffer from a kind of jet-lag for a few days before getting back to normal. I get much more tired spending all day writing than spending 2 whole days conducting a 70-piece orchestra! Conducting is very exciting, I love it. It’s so marvelous, the feeling you get from members of the orchestra. That’s why I enjoyed so much the recent concerts I did in Rome: you have time to rehearse more than the actual written score. Then suddenly the music can take off rather than staying technical and clinical. For instance, the main title of VILLA RIDES! was played well on the record, but in concert when you know that the musicians trust you, everything can come together and take off – it’s an incredible feeling.

So you obviously feel that film music should be played much more often in the concert hall?

Certainly. Even if with film music there is a good deal of padding, there is also a large amount of really great music which not only helps the film but is an entertaining piece of music in its own right. There are pieces of avant-garde music which are called serious music and which maybe will only be heard once in concert and then never again. The film composer has to be far more disciplined and flexible, because he has to satisfy directors, producers, etc., while remaining true to himself – this is most interesting.

The recording sessions for PASSAGE TO INDIA took place at CTS studios, Wembley, over a 5-week period starting from the first week of October. Although recording was over such a protracted period, in fact there were probably, no more than two complete days of recording per week, partly due to the availability of studio space, availability of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and mostly because during October the film was still in the editing stages: so it was really a case of waiting for finished segments of film to become available before the music could be written and recorded. Many a time there would be a large group of copyists at the studios getting the actual notes down on manuscript for recording in the same day!

David Lean was editing the film himself, but unlike his reputation for absolute perfection this time it was being done very quickly to have a completed film for American release in early December. David Lean was very good at describing the emotion and thrust of each scene and exactly what he wanted the music to do. Film is often described as a director’s medium, with the director being in total command. The most surprising thing about David Lean was that although in charge to a certain extent, he was also very mindful of not upsetting the producers by not wanting too much ‘weird’ (Indian) music and being very careful of what music would play over the opening credits for the American Home Box Office. However, Lean is very open to ideas and with Maurice writing the score it becomes more of a collaboration and exchange of views – with David Lean having the final word.

Jarre was obviously under a great deal of pressure, but as always with his wealth of experience remained calm and totally professional. The Royal Philharmonic responded very well to his conducting, despite the long intervals and delays for alterations and sometimes complete re-scoring. Christopher Palmer was Maurice’s assistant and showed great attention to detail while always aware of the overall ambience of each cue. It was impossible to make an objective review of the music from the recording stage due to the very disjointed nature of the recording process, but the general impression of the music was of a very melodious score with moments of symphonic grandeur and touches of 1920’s dance band music, plus some authentic Indian music without being overdone.

The music was scored for differing sizes of orchestra and instrumentation, with a large percussion section and soloing two Ondes Martenot, and Indian instruments played by Ram Narayam. The recording was in digital, engineered by Richard Lewzey.

Maurice seemed pleased with the score and the performance of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and promised to use the same orchestra when next in London, although the choice was very tough as all the orchestras were so good. Maurice in fact insisted that the orchestra receive a credit on the opening titles of the film. He was also very excited about the prospect of doing the forthcoming concert at the Barbican Centre on April 14th with the Royal Philharmonic, where he will conduct his own film music with the emphasis being on the David Lean films.

Finally, there are plans to do a digital recording of the Maurice Jarre music for the three previous David Lean films.

Interesting footnote: Jarre just received the Golden Globe award for his score to A PASSAGE TO INDIA in Hollywood.