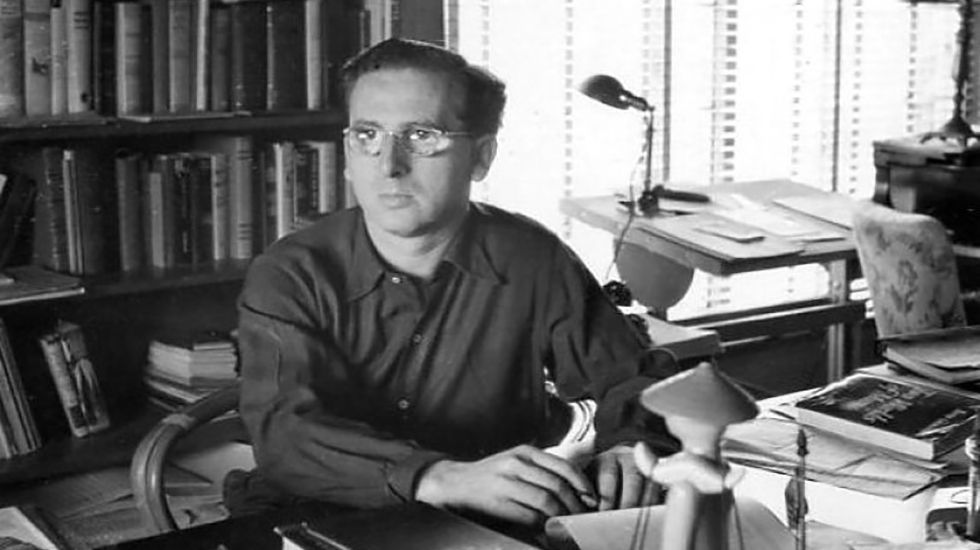

A conversation with John Waxman

A conversation with John Waxman by Luc Van de Ven

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.20 / No.79 / 2001

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

According to Tony Thomas, your father's primary interest was in the concert hall. He regarded film music as secondary, yet many of his concert works have been derived from his own film scores. How did your father feel about his career in films?

Tony Thomas was right but my father felt that he was a composer, whether he was writing for films or the concert hall. Every assignment presented a new musical challenge and opportunity.

He worked rather a lot in TV. What did he feel about the pressure that existed to wrap-up a score in days instead of weeks? The financial restrictions and the small orchestras? Did he score TV programs in a different, time-saving way, or were they just bread-and-butter scores?

He always met his deadlines. The financial rewards were less than in films but most of the television revenue was specifically earmarked for the deficit of the Los Angeles International Music Festival. Waxman founded the festival in 1947 to present each spring (in Royce Hall Auditorium, on the University of Los Angeles campus) the best and newest in contemporary music. During the 20 years of the Festival there were 4 world premieres, 11 American premieres and 53 West Coast premieres; composer-conductors like Egk, Harris, Walton, Milhaud, Shostakovich and Stravinsky came to Los Angeles to present their new works and participate in symposiums with an international body of music critics. I think the small orchestras used in TV recording gave Waxman a challenge, which he enjoyed, to write for groups of instruments other than the big studio orchestras which were normally available to him in his film and concert hall assignments. For example the finale of GUNSMOKE: “The Raid” - Part II reminds me of a chamber orchestra version of “The Ride to Dubno” from TARAS BULBA. Waxman did not take short-cuts in approaching a musical assignment. He was the consummate professional.

Can you pin down for us which segments he scored for each TV series and the year he did them?

Beginning in the late 1950's the scores for such shows as HAWAIIAN EYE and BATMAN were tracked music from films. Most of Waxman’s television scores were either at CBS or Universal. In 1959 he scored “Men and Women”, an unsold pilot episode for the CBS series OPEN WINDOWS. The GUNSMOKE episode that I have already mentioned, “The Raid” Parts I and II, were scored in September 1965. “The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine” segment of CBS's THE TWILIGHT ZONE was done in 1959. Waxman's final CBS assignment was for the documentary series THE 20TH CENTURY: “Lenin and Trotsky” and then “The Mysterious Deep” Parts I and II; the latter was one of the first Jacques Cousteau television specials. At Universal Waxman scored segments from KRAFT SUSPENSE THEATRE and ARREST AND TRIAL.

Your father worked on more than sixty films when he was at Universal. His filmography only lists 13 of these. Which other films did he score at Universal? Were other composers at Universal credited with your father's work? Did this also happen in TV?

No, I do not think it ever happened in TV. The only way to know for sure who scored what cues for which films is to check the cue sheets. Unfortunately, these cue sheets were compiled in the 1950's, and in some cases, twenty years after the film's production. Some cue sheets are not accurate and have been amended over the years.

Franz Waxman didn't seem too fond of the studio system. He switched studios frequently, and from 1950 onwards he worked for just about any major studio. What were his reasons? What did he think of the studio system in general?

To understand why Waxman hop-scotched from studio to studio, you have to look at the progression of his Hollywood career. While at Universal (from 1934-1936) he was primarily the Music Director with administrative responsibilities. He moved to M.G.M. so he could devote all his energies to composition. In 1943 Warner Brothers offered him the opportunity to compose only for dramatic films. When he scored SORRY, WRONG NUMBER in 1948, it was the beginning of his long association with Paramount, 20th Century Fox and United Artists; although he was to return to Warner Brothers frequently during the next nineteen years. From 1948 till the end of his life, Waxman composed as an independent contractor at whatever studio produced the film that interested him.

Who were your father's idols in film music and in classical music? Did he ever have any run-ins with the head of a studio?

It seems to me that he was influenced by both Prokofiev and Mahler but he admired Mozart and Verdi. He had such a renaissance interest in all musical styles that it would be hard for me to be specific on this question. In films he was personally and professionally fond of Bernard Herrmann and Miklos Rosa. During the scoring of THE NUN'S STORY Waxman and director Fred Zinnemann did not agree on the musical concept for the film. Jack Warner sided with Waxman’s approach to the film.

Your father did not get any more assignments after 1962, except for THE LOST COMMAND. Was he tired of scoring films by then? Or were there other reasons?

A combination of reasons. In the early 1960's there were fewer dramatic pictures. He was concertising more throughout the world and composing for the concert hall. He was also living in New York City half of the year.

Were there any major movies, GONE WITH THE WIND for example, that he was not asked to score or would have done if he had been asked?

I cannot think of any. Waxman was scoring REBECCA for Selznick while Steiner was working on GONE WITH THE WIND, although Selznick did ‘track’ Waxman music for “The Battle of Atlanta” sequence in that film.

There have been a number of compilation albums of your father’s work. Do you feel these LP’s are really representative of Franz Waxman’s work? Have you ever been unhappy with the selection of the films and / or themes, and with the musical interpretations (conductor and / or orchestra)?

The answer to that is “No.” Never. Both the Korngold-Gerhardt and the Mills-Queensland albums are fabulous and I am looking forward to the next Mills-Waxman LP this year.

I am delighted to hear that we can expect another record by the Queensland Orchestra. The first Mills-Queensland album will be re-issued as a compact disc, with the following additions:

TASK FORCE

Liberty Fanfares, OBJECTIVE, BURMA!

Suite, PEYTON PLACE

Suite, THE NUN'S STORY

Suite, CAPTAIN’S COURAGEOUS

Overture.

This is not final, but as of this date (August 28th) the second CD will feature:

ANNE OF THE INDIES Overture, POSSESSED Suite, COME BACK, LITTLE SHEBA Reminiscences for Orchestra, DEMETRIUS AND THE GLADIATORS Suite, THE PIONEER Suite (music from RED MOUNTAIN, CIMARRON and THE INDIAN FIGHTER), HUCKLEBERRY FINN Overture, SORRY, WRONG NUMBER Passacaglia for Orchestra.

In addition, Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati “Pops” have just recorded Waxman's THE FURIES Suite as part of their new Western CD.

Composers like Miklos Rozsa sometimes went on location during filming and they did a lot of research. Did your father work the same way?

Yes and no. Franz Waxman has written for the notes to the original TARAS BULBA soundtrack LP that he did find some authentic themes in a music shop in Kiev, while he was in the Soviet Union to conduct the orchestras in Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev. That really was not a location for the film as it was shot in Argentina! THE NUN'S STORY was almost completed when Waxman arrived in Rome in the summer of 1958. However he did do some research on Gregorian chants at the Vatican Library.

Are there any other Waxman projects planned?

Neville Marriner and The Academy of Saint Martin-in-the-Fields will record Waxman's THE CARMEN FANTASIE with Victoria Mullova for Phillips. On May 20. 1987, the 60th anniversary of Charles A. Lindburgh's first trans-Atlantic flight from New York to Paris, the United States Air Force is sponsoring a special concert at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The program will feature the premiere of Waxman's THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS Symphonic Suite in Three Parts with Narrator. The text has been written by the noted British playwright James Forsyth. HEMINGWAY A Symphonic Suite in Six Parts will be premiered in conjunction with the Hemingway centennial.