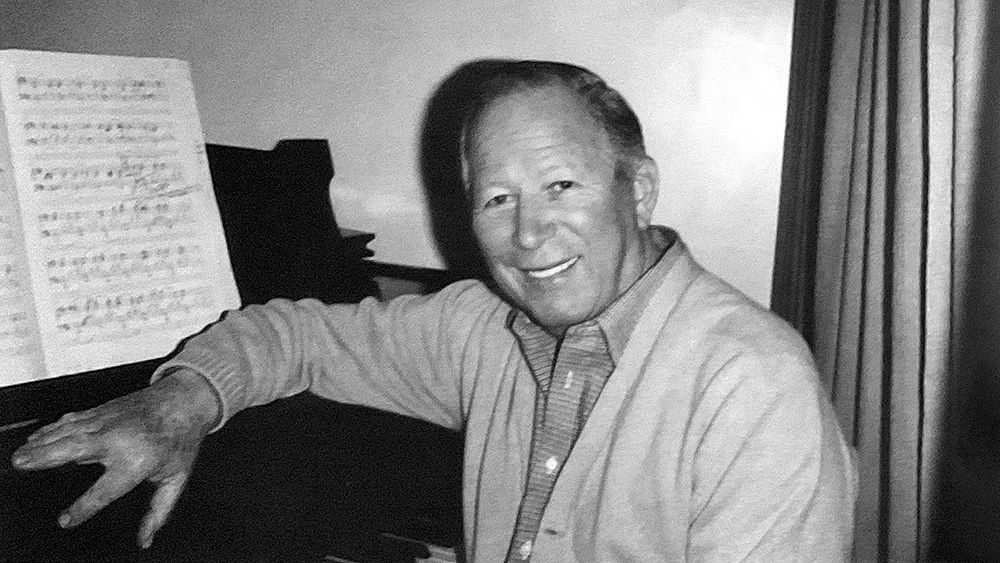

A Conversation with James Bernard

A Conversation with James Bernard by John Mansell

Originally published in Soundtrack Magazine Vol.11 / No.43 / 1992

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor, Luc Van de Ven

For any fan of Hammer movies, the name of James Bernard is a familiar one. His music has added another dimension to the genre of the horror film, and his Dracula theme is as familiar to film music enthusiasts as John Williams' JAWS or Bernard Herrmann’s PSYCHO. Mr. Bernard now lives abroad. He was in England recently when he was doing further work with Silva Screen Records, as well as catching up with some theatre-going. I would like to thank Mr. Bernard for his very kind hospitality in London, and also for consenting to do this interview. Thanks also to Silva Screen, in particular David Stoner, for helping me to arrange this meeting.

When and where did you study music?

I studied at the Royal College of Music from 1947 to 1949; this was after 4 years in the RAF, which I had joined when I left school in 1943. I had met Benjamin Britten during my last term at school, and he had taken an interest in my wild attempts at composing; while I was in the air force, I kept in touch with him. As my time for demobilisation approached, I wrote and asked his advice about further musical training. He advised me to go to one of the music colleges and get a proper grounding in musical discipline. As an ex-serviceman, I managed to get a government grant, and then studied for 2 years at the Royal College of Music in Kensington.

I studied composition with Herbert Howells. He was a gentle and charming man, not in the least severe as a teacher; incidentally, he is nowadays, I think, a much underestimated composer. I also studied piano with Kendall Taylor, but I was definitely not cut out to be a concert pianist! I continued to see Benjamin Britten from time to time, and when I left college I only wanted to compose. Before I left, I was summoned to see the Registrar of the college, a composer called Hugo Anson. (The director of the college was another composer. Sir George Dyson, who, oddly enough, was also the author of the official Manual of Grenade Fighting used by the War Office in World War I). But I am digressing. I went to see the registrar, Hugo Anson. When he asked me what I intended to do on leaving, I replied, “I’m going to compose music and make a living out of it,” - at which he laughed and said, “Oh no, you can't do that; that’s only for people like Vaughan-Williams and William Walton and Benjamin Britten. You'll have to do something else.” Anyway, I kept quiet and said goodbye.

There followed a slightly empty period while I was trying to find my way into some kind of composing work, though I didn't know what. This continued for about a year, during which time I was greatly encouraged and supported by my friend Paul Dehn, who was already a successful writer, and through whom I was moving, somewhat starry-eyed, in the world of literature, theatre and film.

Then, one happy day, Benjamin Britten rang me from Aldebrugh in Suffolk, where he lived. He was writing his opera BILLY BUDD. He said, “Jim, (he always called me Jim), I'm writing an opera and I need someone to copy the vocal score as I write it; it would mean being here with me much of the time, and then taking completed sections up to London to the publishers, Boosey & Hawkes. Will you come and do it?” Of course I leapt at it.

So I went and lived, on and off, for about a year with Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. In my view, Ben was a great composer; he also had a virtuoso piano technique and, just to cap it all, was an extremely good tennis player! His company was stimulating: he had a bright, boyish quality, and a tendency to moodiness which went with his overall brilliance. Peter, on the other hand, had a great serenity and a calming presence; his high tenor singing voice had a memorable quality all of its own, informed by supreme musicianship and great histrionic power.

My time with these two musical giants came as an amazing bonus after my two academic years at the Royal College. Quite apart from many exhilarating evenings when Ben played and Peter sang, it provided an invaluable practical training which taught me the sheer hard work involved in composing. E.M. Forster often came to stay. Another frequent visitor was Imogen Holst. She lived in Aldeburgh, and later, I think, worked full-time for Ben. She was the daughter of Gustav Holst, and was herself a remarkable composer, conductor and teacher. She felt that Ben had continued where her father left off. She was another totally modest and unaffected person - no make-up, and hair parted down the middle with a bun at the back. But her personality positively shone.

So I spent an exciting year. It taught me, as I've said, a great deal about the practicalities of composing. I would have liked to stay with Ben as a personal assistant, but when the opera was finished he made me leave. He said, “Now Jim, if you want to make your own career you must go; if you stay with me you'll be swamped.” He was right of course. However, I wanted to continue to study composition, so Ben suggested that I go to Imogen Holst. She kindly took me on and gave me great help and encouragement. I still went to her when I was starting to work for the BBC.

What sort of work did you do at the BBC?

I composed music for radio plays (television then being very much a newcomer). At that time, Paul (Dehn) was writing plays and features for the BBC; through him I met various other people connected with broadcasting, and so was eventually given my first chance. It was music for a play called

The Death of Hector, based on a episode from Homer's

Iliad. It was written by the poet, Patric Dickinson, and directed by Val Gielgud, the brother of Sir John. Patric had met me through Paul Dehn and, to my eternal gratitude, decided to risk all and try me out. Fortunately Val Gielgud, who was the head of BBC radio drama, agreed. To my relief he liked my music and sent word around the drama department that I could be employed. After that, I got quite a lot of work and wrote music for new plays and for classical plays, among them Marlowe's

Dr. Faustus and Webster's The Duchess of Malfi, both of which have elements of fantasy and horror. Incidentally, I enjoyed composing music for comedies (Molière's

Tartuffe, for example) but my film career was clearly not destined to go in that direction!

Are there any composers in particular that have influenced your style of composing?

I have a wide taste in music, and presumably I have been influenced by an equally wide range of composers. The obvious ones to me are Benjamin Britten, Stravinsky, Liszt, Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Tchaikovsky and Verdi. I love Verdi's operas. Apart from his unforgettable tunes, he invents such wonderful accompaniments - dramatic motifs and strong rhythms which catch a mood and then build it; this is, after all, the essence of film music.

How did you become involved with Hammer Films?

It happened through the conductor John Hollingsworth, who was Hammer's music director from early days until he died, much too young, in about 1963. He had tuberculosis. It was supposed to have been cured but apparently it wasn't. I had known John from when I was in the air force and he was the conductor of the RAF Band. Later, he had become a popular conductor at the Albert Hall prom concerts, and one of the chief conductors of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. He conducted several of my scores for the BBC, including

The Duchess of Malfi, which is a kind of 17th century horror play, full of macabre and magnificent poetry. It was an all-star production led by Peggy Ashcroft and Paul Schofield, so I was able to let fly with the music. Soon after that, Hammer made THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT. This was to have been scored by a composer called John Hotchkiss, but he was taken ill and had to withdraw. The producer, Anthony Hinds, needed a substitute urgently. John played him the

Malfi tapes, Tony approved - and that is how I started with Hammer films (and a happy association with Tony).

For my first 3 Hammer scores (THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT, X, THE UNKNOWN, and QUATERMASS II) I used only strings and percussion. For the BBC, I had used either smallish chamber groups or strings only, so I guess John thought, “we won't trust him with a full orchestra yet - let's see how he gets on with strings and percussion first.” I was very grateful for this. It was agitating enough learning how to work out timings synchronised exactly with the action on the screen, and to get the score finished by that looming deadline! It was not until THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN that I graduated to the full orchestra with brass and woodwind.

Your scores for Hammer productions have a unique and distinct sound. Did you use session musicians or one particular orchestra?

The distinctive sound is, I suppose, due to one’s own particular quirks of orchestration, which is all part of the composition – but I will come to that later. Hammer always used players from the leading symphony orchestras, depending on who was free at any given date. The budget normally limited the orchestra to about 35 players, so one couldn't use an entire particular orchestra, as is often the case with high-budget films. Fortunately, these marvellous players have always seemed to enjoy a break from the concert hall - and, of course, they are brilliant sight-readers which, for film work, is essential. So, even in those early days, I was terribly spoilt and felt humbled by the eminence of the musicians who were playing my music. The leader would often be Hugh Bean (or some equally distinguished violinist), the first oboe Leon Goossens, the first clarinet Jack Brymer - and so on through the orchestra. For my first few films, John Hollingsworth often drew players from the Covent Garden Opera House orchestra.

Your scores for Hammer have been supervised by Philip Martell. Does he also conduct them?

After John died, Philip Martell took over as Hammer's music director, and from then on he conducted all my scores. Between John and Phil, there was a period when Hammer didn't have a regular music director, so Marcus Dodds conducted two of my scores - THE SECRET OF BLOOD ISLAND and, I think, THE GORGON.

Did Philip Martell ever compose any film scores?

He always said that it wasn't his thing. I think he did score a few films, probably before I knew him, and I couldn't tell you what they were. He's an excellent conductor, and is marvellous at knowing and deciding exactly where on a film the music should be placed. Apart from his profound musicianship, he is also expert at hitting (and holding) an exact tempo; this is essential in many film sequences where the points of synchronisation are mathematically planned by the composer, and are absolutely dependent upon the music being played at the marked tempo. When time is pressing, and tension is mounting in the studio, you can understand the iron control demanded of the conductor.

So was he there with you and the director when you were spotting the film?

Absolutely. It was the same with John Hollingsworth. We would go through the film reel by reel, planning the music after each reel. Terence Fisher, who over the years was Hammer's star director, never came to the music breakdowns or the recording sessions. He said, “I'm very happy with what you music boys do. I don't know anything about music so I'll leave it to you.” He was charming. Other directors (though not all of them) liked very much to be at the sessions. Joseph Losey had an extra-ordinary and arresting personality, as one might guess from his films. He was much involved with the music for THE DAMNED. I liked him immensely, though he could be difficult.

Do you orchestrate your own scores?

Yes, I have always done my own orchestrations, with a few brief exceptions which I will come to. I know that in the United States it is quite normal to use orchestrators, and obviously if a film requires a great deal of music, there are situations where the composer couldn't meet his deadline without the help of an orchestrator. I have occasionally used an orchestrator for a specific reason. I'll give you an example: in THE KISS OF THE VAMPIRE, do you remember the scene where there is a sort of Vampires' Convention and vampires from everywhere assemble in Dr. Ravna's castle for a masked ball? For this we needed a sequence of waltzes in the Viennese style. I composed the waltzes before the rest of the score so that they could be played on a piano for the actual filming. I then needed to press on with the main score, so I asked John Hollingsworth whether we could get someone to orchestrate the waltzes. Douglas Gamley, who is of course himself a composer, came to my rescue and orchestrated them perfectly. He also played the solo piano music which I composed for the film. As far as I can remember, the only other time I used an orchestrator was for the rock music in THE DAMNED.

I must add that every time I do a score I am full of doubt, and spend hours dithering and pondering whether, for example, a certain phrase should be played by the bass clarinet or the bassoon, or even the double-bassoon - or would a solo cello be better after all? When possible, I like to sketch out the entire score first, working out the timings and making notes of probable orchestration. At this stage, the music is written on just two or three staves, or sometimes more if the music is complicated. Then I embark on the orchestration, when I sit down with the 24-stave manuscript paper in front of me and start to fill it up. While I do this, I still have second thoughts and alter things - so you can understand why, to me, it is all part of the composing.

When do you prefer to come in on a film?

As early as possible. It's helpful if I can get a script, because then I know what the film is about and can start to think of possible themes. I am delighted if there's the chance of a romantic theme to make a break from the tense dramatic stuff. Of course, one has to wait for the final cut of the film before one can get exact timings and start on the detailed score. Even then there are occasions when one has planned out a section absolutely brilliantly, with all the timings just right (or so one thinks), and then the editor rings up and says. “I'm awfully sorry, we've had to cut 19 feet out of that scene.” Out of the window go all those precious timings and one wants to scream - or rush for the vodka!

Have you a particular favorite film score of your own?

Let me see. I was quite pleased with SHE; it was a different sort of score and gave me a chance to be romantic. I love that fantasy element, which is not necessarily horror. I also quite like some of the music for THE DEVIL RIDES OUT and obviously I'm delighted with the success that the Dracula scores have had. In each score there are certain bits that I'm pleased with, and other bits with which I'm not so pleased. There is always something that later you think you could have done better, but I think overall I would choose SHE and THE DEVIL RIDES OUT, perhaps followed by THE GORGON and THE DAMNED, and possibly THE KISS OF THE VAMPIRE. Just recently I saw THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN on television. I thought the film was excellent and was unexpectedly impressed by some of the music!

You like opera and go to the theatre. Do you collect on buy any soundtrack albums?

No, I must confess I don’t. Perhaps I should, but I have never been a dedicated record collector and, when I do buy a record, it tends to be classical music or one of my favorite jazz performers such as Nat King Cole or Ella Fitzgerald.

Other composers who work in films who have been asked if they go to the cinema have said that they do not go in case they are influenced by other film scores. What do you think about that?

I love going to the cinema. I don't go often enough, and I am always very interested in the soundtrack; after all, if you admire something and it influences you, there's nothing wrong with that. Each composer has to be influenced by something or someone, unless he or she is a total original genius like Beethoven, and I'm sure that even he must have been influenced by somebody. I agree one does not want to find one has written the exact tune that someone else has written! That’s something to guard against. I'm not talking about horror stuff now, but about trying to compose a simple tune with immediate appeal. For this, one needs to use a more or less normal diatonic scale, which consists of only seven different notes, with a possible five extra chromatic notes. So it's not surprising that lots of tunes remind one of other tunes. Many times I have written a tune and thought, “I'm rather pleased with this,” and then thought, “Oh Lord, no, - this is something out of Puccini”. Then I have had to rush to somebody to ask them. In the days when I shared a house with Paul Dehn, who was highly musical, I'd say, “Paul, come quickly. Is this the love duet out of Madame Butterfly?” - and he would say either yes or no. So one has to watch out, but, for me, that’s no reason for not collecting soundtrack albums or for not going to the cinema.

Were there any scores that you found difficult to compose?

Nothing leaps to mind, although every score seems difficult at first. You think to yourself, “I'm never going to be able to do this,” but then, slowly, you get into it. I have on occasion been stuck, particularly if I have been working very much against time. I know I had a hard time on SHE. One thing I have always admired in the Hammer films is that they never, in my opinion, use too much music. But in SHE there was quite a lot of it. I remember working more or less through the night towards the end of that score and getting very stuck at one particular point. But then I compelled myself to have a few hours' sleep, and when I came back the problem was quickly solved. I think sleep is the answer. One must let the subconscious take over.

When you write music for a film, do you do it in any particular order? Do you start at the main credits and work through to the end titles or do you score it in no particular order at all?

I much prefer to start at the beginning and work through to the end. Then I can try to develop my score symphonically - or maybe that sounds too grand! Of course, music is sometimes needed for use during the actual filming; for instance, the waltzes in THE KISS OF THE VAMPIRE, or the music for the belly-dancers in SHE (the scene in the Cairo night-club towards the start of the film). But these are usually separate pieces, so they don't disrupt the build-up of the main music.

Are you working on anything at the moment?

Encouraged by David Stoner of Silva Screen Records, I have been going through music from past scores, and preparing pieces for a possible second volume of “Music from the Hammer Films”. There have been quite a few requests for this, so I think Silva Screen have it in mind. I am superstitious about counting chickens before they are hatched, so I'll say no more at present - except that I have now orchestrated the aforementioned waltz from THE KISS OF THE VAMPIRE myself (so as not to cheat).

Do you still get scripts sent to you?

I have usually only been sent scripts of films which I have already agreed to do. However, some months ago I was sent a script from America which I read with interest. But it was to be an independent production, and so far I have heard no more.

If an offer came your way and you thought it was a good film, would you do it?

Yes, I hope so. Having been browsing in tropical sunshine for some years, I feel I've stored up quite a bit of energy.

Have you ever pulled out of a project?

No, never. I have always liked to be asked to work, so I've never pulled out of anything - nor, touch wood, have I had a score thrown out. I mean, that has happened to the very best composers - far better than me.

It happened to Sir William Walton.

Yes. I knew him quite well and he was terribly upset over the rejection of his BATTLE OF BRITAIN score.

I personally prefer the Walton score.

It's brilliant.

In 1951 you won an Oscar…

Yes, but it wasn't for music; I had hardly started my composing career. I won it with Paul Dehn for the year's best original film story - SEVEN DAYS TO NOON. I'm not sure whether that category of Oscar still exists. Paul and I thought it up together, Paul committed it to paper and we sold it to the Boulting Brothers. It was before Paul had started writing screenplays himself, though he was already a well-known film critic. We got an Oscar each, but no question in those days of flying to Hollywood and taking part in all those glittering proceedings! The first we heard about it was in the Evening Standard; then, a week or two later, a representative of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences arrived at our Chelsea house with a cardboard box containing our Oscars - not even a ribbon! Three large gin-and-tonics, and that was our Oscar ceremony!

On the LP of SEVEN GOLDEN VAMPIRES there is a march theme that I cannot remember hearing in the film...

You're right. I wrote it for the LP. I think it was Philip Martell's idea to have something to start the record, like an overture; it's derived from some of my “Chinese” music in the film. If I remember rightly, it is repeated at the end of the record.

What is your opinion of the use of synthesizers as opposed to orchestral scores?

I think they can be very effective. I've never used one but that is not because I wouldn't, if the director particularly wanted one. Hammer have always preferred orchestral scores, which are more emotional and, in my opinion, much more suitable for gothic horror, such as the Dracula and Frankenstein stories. I did use a type of electric keyboard in THE GORGON. It was a Novachord, it was played in unison with the soprano voice to produce the call of the Gorgon, which lured victims to their stony doom.

I have always wondered why the scores that you wrote for Hammer, in particular DRACULA, were never released on record at the time of the film release.

I think that at that time soundtrack albums had scarcely been introduced in England, except perhaps for American musicals, or epics like BEN-HUR.

I have also wondered why Hammer didn’t have their own record label...

For the same reason. When Hammer made their first great success back in the 50's, I doubt whether anyone in England (except filmmakers) ever thought about soundtracks, let alone records of them. I remember in those early days I would sometimes be talking to someone at a cocktail party and they would ask me what I did. I would reply, “I'm a composer and I write music for films” - to which the answer would be, “Oh you mean background music; I'm afraid I never listen to it.” End of conversation! Since then, film composers have definitely gone up in the world.