A Conversation with Ernest Gold

A Conversation with Ernest Gold by Randall D. Larson

Originally published in CinemaScore #10, 1982

Text reproduced by kind permission of the editor and publisher Randall D. Larson

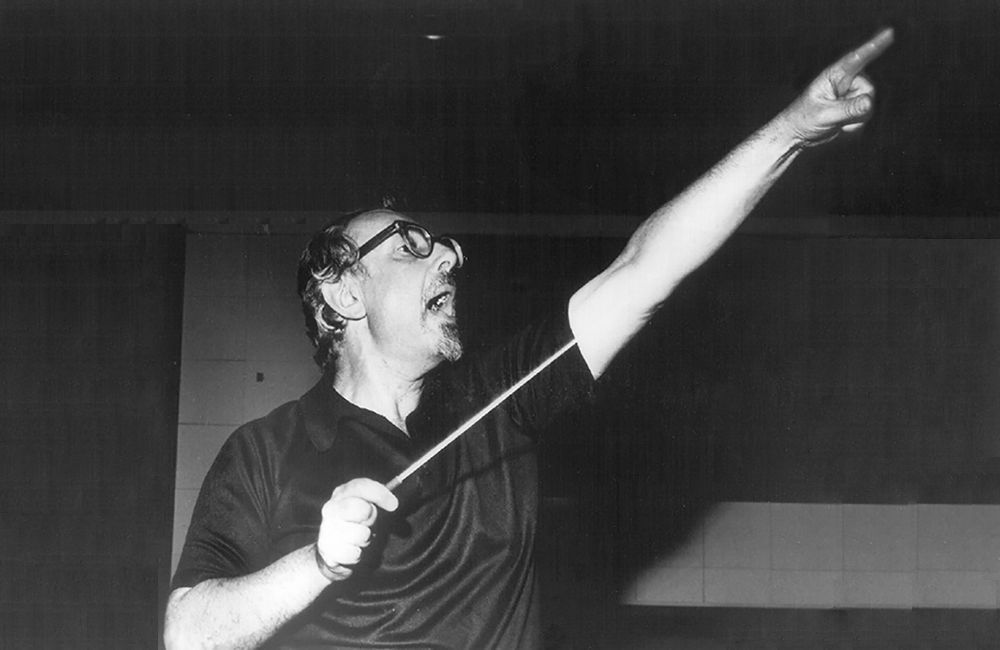

Ernest Gold was born in Vienna, Austria, on July 13, 1921. He began to study music at the age of six and went on to study at the State Academy of Music. When Hitler invaded Austria in 1938, Gold left for the United States, where he worked first as a piano accompanist and later as a songwriter of popular tunes in New York. Eventually he arrived in Hollywood, where he was quickly put to work as a composer for Columbia Pictures in 1945. Gold endured the assembly-line production of numerous B-movies until achieving acclaim with his score for Stanley Kramer’s ON THE BEACH in 1959. The following year, Gold earned world-wide fame as the composer for Otto Preminger’s EXODUS, for which he won the Academy Award for best score, in addition to two Grammy Awards, for best soundtrack album and best song. In addition to composing for the screen, Gold has also served as the musical director for the Santa Barbara Symphony, conducted his own concert music, such as the acclaimed ‘Symphony for Five Instruments’ (1952; recorded in 1973 on Crystal Records S-862), and has contributed to the pages of ‘Opera News’ and ‘Musical Journal’. Gold has also travelled numerous times around the world to conduct his new works.

The following interview was recorded during December 1981 and January 1982. Mr. Gold speaks with a marvelous Austrian accent and, while accustomed to a modern musical orientation, has never lost track of his Viennese musical heritage. I am particularly grateful to Ernest Gold for taking the time to discuss his career at such length. [Addendum: Ernest Gold died on March 17, 1999 at the age of 77].

How did you acquire your interest in music?

My interest in music is something that was really there almost from my birth. I came from a very musical family. My paternal grandfather was a graduate of the Conservatory in Vienna, an excellent pianist (though he was a civil servant for a living). But he was an excellent pianist and a composer of some very, very good light Viennese type music, marches and waltzes and things like that. I was the first professional, incidentally, in my family, so all the people that I will now discuss, that came before me, were highly accomplished and schooled amateurs such as you find very little these days anymore, where amateurism merely means “not schooled”. These people were all highly educated and schooled, and the reason they didn’t become professional was primarily because they had to make a living and didn’t want to take a chance on the uncertain future of a professional musician.

Now, as I said, my paternal grandfather was an extremely well educated pianist, composer of light music. My father was an accomplished violinist; by the time he was twelve years old he already played the Tchaikovsky violin concerto, and also an excellent composer and pupil of Richard Heuberger, whose operetta, ‘The Opera Ball’, of course, is to this day a very favorite piece. He, again, was also doctor of law, and was an executive rather than a professional musician, though as I say he was highly accomplished. In fact, I received my very, very rudimentary training in music theory when I was young from him. My maternal grandfather was not only the President of the Society of Friends of Music in Vienna (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien), an organization that had originally been started by Brahms, but he was, again, a fabulous pianist who, in fact, played publicly once a year, within the scope of the concerts given by that Society. He was a composition pupil of Anton Bruckner, and composed all his life. He was more of a serious musician than my paternal grandfather, and a very interesting man. Incidentally, he also had a Ph.D in chemistry, and he made his living as an industrialist; and after he retired he studied medicine, and became an MD just out of Interest, so he had three doctorates – music, chemistry and medicine. My mother was a trained singer; again, she did not practice it but she had taken vocal lessons and also played the piano, although not exceptionally well. So, you see, music was really all around me as a kid, and very naturally, from that background, I decided that I was to become an aviator! (Laughs). My musical interest really only began at the age of twelve, but from then on it really went wild, though I did write a couple of melodies – I shouldn’t say write; I started putting them together on the piano when I was five, and my dad wrote them down for me.

You started appreciating music in motion pictures at an early age, didn’t you?

I was split about fifty-fifty between going to the movies instead of doing my homework, particularly musicals (and even then I was already quite conversant with the names of people like Max Steiner and so forth), and going to the opera. Between operas and motion pictures my interest in the dramatic application of music was very early. I was totally enchanted by American popular music, and I went to see all the old, great Fred Astaire musicals, the Warner Bros. musicals; and I didn’t just see them once, but I saw them innumerable times, until I could play all the songs, almost with the arrangements that they had, by ear on the piano. That, to me, was the most exciting form of cinematic music.

Also, the scores that the German pictures had were very negligible, usually an extremely small group and very sporadic, but American pictures were scored, of course, in a much richer and a much more impressive way, and that was a big thing for me and I listened to the scores quite consciously.

It has been said that your interest in writing music for films yourself didn’t flourish until critics dubbed your 1943 Piano Concerto as “sounding like movie music”.

Correction – that Piano Concerto was performed in 1945, in January, and I arrived in Hollywood very soon thereafter, in late June or early July. Anyhow, this is not correct. My interest in writing film music actually was quite early. I was a popular songwriter then and I paid for my studies in New York from the money I made from writing songs. I had a few quite successful ones, and had hoped, somehow, that Hollywood would send for me, in a rather naive way of figuring if you had some hit songs they would immediately send for you and roll out the red carpet. And when I realized that this wasn’t going to happen, I simply took matters in hand. At that time, I had given up the song writing business because I was bored by having everybody tell me how a song should be written – people who may have had practical commercial knowledge but had no sense of music, really. I had kind of outgrown the form as a primary form of musical composition, and so I simply packed up and came out here to try my luck.

The Piano Concerto incident was of course the trigger that actually got me off my butt and out here, but the idea of doing this was quite a long time in coming. I was a professional songwriter roughly from when I arrived in the USA – I came late in ‘38, had my first published number by late ’39, and went through about 1943. Then I stopped – meanwhile I had studied a lot of theory, I studied conducting, and I rediscovered my European roots, too. After I came to the United States all I wanted was popular music; of course, I was a teenager then. But I gradually recaptured my interest in serious music, and with that my interest in writing popular music diminished, and I made a living by teaching music classes in some private schools, and giving some private composition lessons to people, but that was not very exciting, although I did a lot of writing. Then the whole thing came to a head after that incident with my Piano Concerto.

What sort of assignments did you first receive in Hollywood?

Small ones, naturally. I was very lucky, in that I received my first assignment within two weeks of coming out here, which was partially due to the fact that a lot of pictures were being made, and many of the fellows were in the Service, and composers were really needed. And I was a new face from New York, which carried a certain prestige, had a piano concerto played there which pleased the people here who said it was “like movie music”. Of course, that meant something very good here, whereas in New York it was the kiss of death! As a consequence, it was very quickly that I latched onto something. I didn’t do very many pictures, there were long pauses in between, and they were, of course, very small pictures, but it was very exciting to me because suddenly I was assured of performances, I was paid, much more than I had ever earned giving lessons, and it was altogether a rather intoxicating time, I signed with MCA for representation, and gradually just got going. But I did nothing but small pictures for almost thirteen years before things began to change.

What was your impression of working on assembly-line B-movies in the 40s and 50s?

There was no impression. A picture was a picture, to me. I used to say that any picture I do, for me, is an A picture. I lavished exactly the same care, I felt exactly the same excitement, and I did everything exactly with the same enthusiasm for the medium in those days that I had later on when I did bigger pictures. It was exciting, it was the Movies, it was composing, it was conducting the score; I’d always felt a picture is a picture is a picture – some are good, some are not good; if it’s too bad, I won’t do it. I just did every picture the best I knew how, trying to do justice to its particular story line, locale and time.

How did you meet the challenge of supplying good music for the films that did not always seem that concerned with aesthetics as with getting it done on time?

Well, this is a problem that of course has been always a problem in Hollywood; the producer wants something that he feels works for the picture and he wants it on time, although the pressure was not that great in the earlier days. The way it used to work was that you started the score and when you had it pretty well underway, you then set the recording date; now, when my agent calls me the first thing he tells me is the recording date, and then we start talking about everything else, which is not very good. But, it was always a hassle, and I’ve always felt that there is only one person that I really have to please in all of this, and that is me. If the producer is pleased as well, so much the better. I was fortunate that frequently what pleased me pleased the producer or pleased the audience, but you cannot do anything that makes any sense artistically (and that to me has always been the most important thing) by pleasing other people at the expense of yourself. Pleasing other people when you yourself are pleased is great.

So I’ve always written the best music I know how, sometimes working awfully hard and knocking myself out when I could have, with a little less effort, turned something quite decent in, probably, but I wouldn’t have been very happy with it, since my self esteem is very much tied in with what I think of myself as a composer. But it does mean working long hours because usually we haven’t got the luxury to rewrite a piece of music four, five or six times until you feel it is right, or spending as I did once, in fact, literally six hours on two notes! I was never one to feel that time was any consideration. I just worked until I was exhausted and started the next day at four in the morning, if necessary. But there wasn’t ever a cue I turned in that I wasn’t entirely happy with and where I couldn’t say that this is as good a piece of music as I am capable of. Whether it is good in an absolute sense is of course not for me to say, but I have always felt that unless I can satisfy my own demands – and they are pretty high; I expect a great deal of myself – in the sense that at least want to live up to my potential, whatever that may be. So the challenge has simply been trying to make sure that I have enough time. There have been quite a few pictures I’ve turned down because there wasn’t enough time for me to do the type of job that I felt I wanted to do, and I had to give up a lot of money in the process, but time is the one item that was not negotiable. If I can’t do it right, I don’t want to do it.

What sort of musical approach did you take in scoring these B pictures?

I approached them in exactly the same way as any other picture. If the story in a B picture was a cheap kind of a story, then the picture needed a, quote-unquote, “cheap” score”, because, no matter what the story, the score has to support it. If the picture was silly, then it needed that kind of a score; but there’s no special approach. You take each picture and you try to do justice to what it is.

The only differences are the budgets. If there was a very small budget for the orchestra, I could not have used a large one. I had to use a lot of imagination to get the expression and the effects I wanted from the small group. But it could have been a double A picture with a small music budget, or for artistic reasons I might have decided to use a small orchestral combination, and then the problem would have been the same. So there is really no inherent difference.

What sort of influence did other film composers exert upon your work?

That is an extremely difficult thing to answer, because you absorb things all the time, naturally, in everything. I’m not always aware of what influence a given composer has, but I would say that I was influenced by the things that excited me, scores of Franz Waxman, some of the work of Bernard Herrmann. In my very young days I was very taken by Max Steiner, whose influence on me, however, by the time I got to score had diminished a good deal, except in TOO MUCH, TOO SOON, where I deliberately wrote the type of score that had a little Steinerish feeling to it, simply because of the type of story it was. It was about the old Hollywood of which Steiner was of course such an important part, and so, again, because of the picture what I did turned out to be somewhat Max Steinerish, although I must say in no sense did I consciously think of Max at the time.

You studied with George Antheil, didn’t you?

I began studying with him about 1947. I studied for about two years. I met him while I was under contract at Republic Pictures, and he did a picture there and they needed somebody to orchestrate a few cues for him, because the time was running out. The people who were actually doing the orchestrating had their hands full, and I was called in, and he was very impressed with my work. So one day I just called him up and said, “Look, I’m a composer of serious music as well, I’d like to show you what I have.” And I went to his house, he listened to my work and said to me in his inimitable way, “Ernest, you’re full of talent, but you don’t know form…” I can’t remember what he said but he used several four letter words right there! And so I studied with him and we worked on some counterpoint, mostly the large symphonic forms, he was great at that. I orchestrated many of his pictures after that, and I also conducted some of his scores, and we were friends until he died in 1958.

I’ve heard that it was his recommendation that got you the assignment to score Stanley Kramer’s ON THE BEACH?

Not so. George was in New York doing a television show when Stanley did a picture called THE DEFIANT ONES that needed about five minutes of rock & roll 1950’s style. George couldn’t do that type of work at all, and besides he was busy with the television show. I had talked to Stanley on a number of occasions, and written him some letters too (of course he knew me from working as George’s orchestrator and he was impressed with my work that way), and I always felt myself in a strange position, so I used to say to Stanley or write to him, that while I’m in no way wishing to compete with Antheil, if there was anything that came up that he didn’t want Antheil to do for whatever reason, I would really give my eye teeth to do a picture for him, because Kramer then was the number one producer in Hollywood. So when George was not available I did THE DEFIANT ONES, and Stanley was very impressed with what I did, even though it was so little. The next big picture was ON THE BEACH, which George was supposed to do, and he died of a heart attack before the picture was ready for music. By that time Stanley was ready to give it to me, and that’s how our association started. George did say to Stanley that I was his most talented pupil, but he never directly recommended me for pictures to Kramer because obviously be himself wanted to do them.

You almost turned down ON THE BEACH because Kramer wanted ‘Waltzing Mathilda’ used throughout the score. How did you meet this challenge and utilize the song in an effective way?

This is true. When Kramer told me he wanted ‘Waltzing Mathilda’ all over the place, I thought: “My God!” I mean, here I have the chance to finally do a big picture after all these years and I’m stuck with a piece of music that I personally detest! And then I said, no, I’m going to make it a challenge, and I’m going to call upon all my skills as a composer by variation, reharmonization, development, every musical device that I was aware of, to use that as a bit of thematic material and confine it essentially to say: “Australia”. I did write a theme, which was a love theme, and I did write themes for various other characters, so that in a sense I demoted ‘Waltzing Mathilda’ to creating local color, but it was right for the picture. It would have been wrong to use it for everything. And that’s how I worked it; in the end I was rather pleased with it because I did really pull things out of that theme that I didn’t know were there, potentially, so it was a great bit of discipline for me, and it worked out to everybody’s satisfaction.

How closely did Stanley Kramer work with you on subsequent films?

No closer than on anything else. Stanley is not essentially a music person. He has little ear for music but he has a great film sense, and we developed a marvelous modus operandi. Stanley turned the picture over to me, spotted the picture, then the secretary typed out the complete spotting notes and I’d go into Stanley’s office and we’d discuss it. Usually there was nearly total agreement as to where the music should go; I would say that, out of a 45-minute score, if there was some difference of opinion about maybe ten or twenty seconds, that was a lot. Sometimes I felt a certain scene didn’t need music and Stanley felt there ought to be music; of course I would write it because we could always dump it in the dubbing if it proved that I was right and Stanley was wrong. On the other hand, it was good to have in case I was wrong and Stanley was right. But the disagreements were very, very minor.

When we recorded, Stanley would come in and listen to one or two cues, and then go to his office, leaving it to me to finish the recording on my own. I had, virtually, one hundred per cent control over all musical matters because Stanley was one of the people who really know how to delegate responsibility, trusted the people that he worked with. There wasn’t any of this trying to control every phase; he was the opposite of the now-current auteur theory. So it was very easy to work with him and very pleasant, because I was my own master.

IT’S A MAD, MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD is an especially fun score to listen to. What was your approach at providing music for this zany madcap comedy?

There were two considerations very important to me. One was that, very obviously, a picture of three and a half hours length done in Cinerama and six-track stereo sound couldn’t be properly supported by a small group such as, say, a television comedy would require. So I decided I needed a large orchestra, and I went to Stanley and said I wanted to engage the entire Los Angeles Philharmonic, a hundred and six men, which he actually did, and we recorded the score with the Philharmonic. The soundtrack album, however, had to be done over because there was a conflict of recording commitments between United Artists (who were responsible for the soundtrack album) and the contract that the Philharmonic had (which was with London Records). So we couldn’t use the actual soundtrack but had to do it over again.

I used a somewhat reduced orchestra for that, but it wasn’t greatly reduced. I would say we probably boiled it down to sixty-five – we didn’t need such large string sections, of course, for a record album as we would filling a whole theatre with six-track stereo sound.

The other thing that the music had to do was to provide a measure of continuity. The picture, as you will remember, cut back and forth between the various groups of people, all of them in a mad rush to get to that money that was supposed to be buried near San Diego, and that made the picture choppy. So I decided to write long melodic lines that would kind of be the gluing factor, and to play the different scenes in different ways by the way I treated the melody and by the accompaniments – so that the accompaniment and figurations usually took due note of the different scenes that they were accompanying. But the melody was the unifying factor, as indeed, in a large sense, the theme of the hunt for that money was common to all the various parties involved in that mad car chase. So, again, in a sense, the musical technique mirrored the actual dramatic situation in the picture.

It was a back-breaking job! I’ve never in my life been so tired as I was in that; it took some nine-hundred pages of orchestra score, roughly the same number of notes as was required to write Das Rheingold, and now I know what Wagner must have gone through with his music dramas! Six months of very, very hard work and all I could do was to dream of the day I would lie on the beach somewhere and just soak up the sun and not have to push a pencil and not have to formulate yet another musical idea. It was exhausting but it was great when it was finished. It was a very satisfactory job for me and I got a lot of gratification out of doing it.

Did you collaborate at all with Mack David, who wrote the lyrics for the title song? How did the need for lyrics affect your composing of the title theme?

Well, there was nothing to it. I wrote the music without any lyrics, and we decided after I had written the tune to give it to Mack David to provide lyrics. I didn’t even know who was going to write the lyrics at the time I wrote the tune. I knew it was going to be a song, and having spent a fair amount of my early life as a songwriter, I knew how to write a song. So I wrote a song melody, which I thought was right for the picture, would work instrumentally, and would also be capable of being sung. We handed him the music, he wrote the lyrics. It was not a collaboration in the sense of working together, it was simply a question of my writing a melody first and he supplying the lyric afterward, which happens quite often. For instance, in THE SECRET OF SANTA VITTORIA, I wrote a purely instrumental number and as an afterthought we decided to have it sung in the main titles. We had an English lyric written, got it re-written in Italian, and then after the orchestra had already recorded the main title, Sergio Franchi came in and overdubbed the vocal line.

Your score for EXODUS was an especially moving composition. Otto Preminger hired you at the start of the film, instead of at the end, as most filmmakers seem to do. What sort of preparation did you accomplish during the filming?

Tremendous preparation. For one thing, I knew nothing about Israeli music, so when I got to Israel, a man was engaged and took me around to concerts, folk music, nightclubs, rehearsal of the Inbal dancers, for Yemenite music. I studied Arabic music, I made copious notes on the instruments, the harmonic and melodic procedures, and I went to recording sessions of native music. I really steeped myself in it, and it paid off. I had a folder, at the end, and it must have been at least an inch and a half or two inches thick – I think I could have used it for a doctoral dissertation. It was a tremendous amount of work.

I wrote thirty-three themes. Any character in the picture, any situation I could think of. I just kept writing and writing and writing, and the purpose of this was to really get inside this thing because I knew I wasn’t going to have too much time once the score was demanded for real. So by the time I got through, as I said, I had thirty-three themes, of which I actually used in the picture only six. By way of a funny postscript, the thirty-third theme, which I wrote simply because I had more time and nothing to do, turned out to be the Exodus Theme! It was an afterthought, and it partially consists of some small motives found in other themes – it’s a synthesis, in a sense, of the essence of the thematic material that I had created. I decided to make that into my main theme. Many of the other themes that I never used in the picture of course I have used since, either modified somewhat or as I had originally conceived it, in other pictures as turned out to be suitable.

I got to Israel first around Easter time, in the middle of April. I stayed there until June, then we went to Cyprus for two weeks. And then I arrived In London on the fourth of July, with this tremendous amount of material in sketch form. When I began to get the timings, I finished an hour and a half of music in slightly over four weeks. Now, I didn’t make my own orchestrations; they were made by Gerard Schurmann, a very, very fine young English composer. We’ve become great friends and he’s orchestrated a couple of more things for me, He doesn’t usually orchestrate other people’s music, he does his own pictures; but, of course, he made marvellous orchestrations, and that made my life easier. I did indicate many things, but not everything, and that saved time, It wouldn’t have been possible without this preparation, without a tremendous amount of creative thinking going on first, because I never had to stop and think “well, what am I going to do here, what kind of theme?” I had my entire material ready to go and all I really had to do was to modify it so it would fit the individual scenes.

So this kind of arrangement had very definite advantages?

Yes. I think any producer who can hire a composer early on is much ahead of the game, because there is no substitute for a gestation period. When you run the picture once or twice and you have to start writing, you haven’t got any preparation. You haven’t got any time, you’ve got to grab the first thing that comes to mind, and that is not the way to do good work.

How closely did you work with Preminger? Did he have any preferences on how you scored the film?

Again, as with Stanley Kramer, no. He came up to my room a number of times while I was sketching, and while I was composing the music, just to see that I was doing something. I would play him one or two themes – maybe I played him a total of three minutes of music – he was satisfied that I was not goofing off, we talked about a few other things and he left very satisfied. He did not impose any ideas on me at all. At the recording session, however, he kept me on a very short leash, and he made me change a number of things, and I learned a tremendous amount from that experience. At the time I was very unhappy, because I felt that he was kind of butchering up some of the things I had done, but in retrospect I found that his grasp of what music should do dramatically was excellent, and that by following his various dicta I really improved the dramatic support that the music gave to the picture, so I would say at the recording session he made himself felt, but not until then.

There seems to be a combination of traditional Israel and Arab musical styles as well as your own musical ideas. How were these combined during composition and orchestration?

I used no material that was native, except for the chant of the Muezzin up in the Minaret. What I did do was to take a great deal of care in the designing of the themes to use the scales, the rhythmic bits, the form of articulation, even orchestral sounds which I had to approximate. For instance, there is a strange whining oriental instrument that I couldn’t find any place, so I used a muted violin together with a recorder to create a similar sound. There may have been one or two little songs that the kids sang that were traditional, but the score itself was entirely original.

You scored several documentaries and cartoon shorts in the early 1950s. What were the conditions under which you worked on these assignments, and what sort of musical approaches did you take?

The conditions under which I did the cartoon shorts were vastly different from those under which I did the documentaries. The documentaries were made by friends, such as THE ARCHITECTURE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT and Curtis Harrington’s two experimental pictures, THE ASSIGNATION and THE PICNIC. The cartoon shorts that I made were done for UPA and were done like any other picture. What I tried to do in the cartoons was not to use the usual wall-to-wall music approach, where the music starts at the beginning of the cartoon and keeps going, but I tried to treat it like a miniature feature. I spotted the picture, I let the music stop, I brought it back in again, I played the scenes – of course you work in a somewhat different way on a cartoon because there you have what is called bar sheets. In the case of GERALD McBOING BOING’S SYMPHONY, actually I wrote the little so called symphony – this miniature composition that should give the feeling of a classical symphony – first, and they animated to the music. So the music was recorded first for that particular piece, which from a composer’s point of view is as close to heaven as you can come!

But usually, you wrote to the picture.

Of course this was in the days before videotapes, so what I had was a very, very detailed description of the music, with exact clicks (cartoons have to be done completely to clicks because the action has to be so precise), and I’d compose the music. But I tried, as I said, not to do it the cartoon way but to try to do it like a miniature feature which I felt was in keeping with the rather unusual (for the time) character of those cartoons.

The documentaries that were done were quite different, I treated those like any other picture, except of course they were done on a shoestring. I believe one of them, the Frank Lloyd Wright thing, was actually recorded at my home. I hired a string quartet, and we did it to the stopwatch because obviously there was no question of projection or a music cutter – there was just no money. And since it was a completely non-commercial feature, I just had four good musicians, it was recorded on a decent portable tape recorder, and then transferred to film and put in the picture.

On the other hand, some of the other things that I did were done in a recording studio and were more professional. But I took care to let the music support the picture and give a feeling. For instance, the Frank Lloyd Wright thing was an architectural picture so there is, of course, nothing emotional that can be done, but still you can add some warmth to it instead of just providing noise on the soundtrack. I remember vaguely that there was a scene in which the living room was demonstrated, with a fire in the fireplace, and so I wrote a little piece that sounded like classical chamber music to go with the image of a cozy living room with a fireplace, giving a sense of people that might relax in front of a fire and turn on the hi-fi and listen to a quiet classical quartet by Haydn or Mozart, something like that. I used a little larger orchestra for that scene.

You’ve said that you dislike scoring for television. Why is this?

Well, now you’ve got me on my favorite subject! The reason I hate television has many, many reasons. I will take them in no particular order, just as they come to mind. Of course, the first one is money. The composers, regardless of how well-known you are, or how great your credits are, they’re all paid pretty much the same, and at a rate that is perhaps one eighth to one tenth what you would get for the equivalent work in a theatrical motion picture. Having spent a lifetime perfecting my art, I really resent being paid for my efforts, experience and talent, the same that any newcomer doing his first or second television show is paid. This is all part of the machine syndrome. It’s like you’re being put in a sausage machine and chopped up and you come out on the other end as a sausage together with everybody else.

Just to give you a concrete example – and I’m not talking about myself now, but of the profession as a whole – a first-rate composer will get $10,000 to $50,000 for the composition of a motion picture score for a two-hour movie. The same composer will get $5,000 for composing a movie made for television, and he has to contribute the orchestration for that price as well. There hasn’t been an increase in prices in maybe ten years. I wish to God that there weren’t composers around who need the money and who will go it for anything just to get the work because that way we have no bargaining strength.

I’ll make a long story short. I did a picture called THE SMALL MIRACLE, and when I got through I figured that I had $345 to show for the job that tied me up for three weeks. That is less than you get right now for unemployment insurance! Once in a while a producer who really wants a composer might get him $7,500 for a movie-of-the-week, and I think $10,000 is about as much as anybody has ever paid for a movie-of-the-week, which is still only twenty to twenty five percent of what the composer would get for the same amount of work in a theatrical motion picture.

The next thing I hate about television is the rush. I did THE SMALL MIRACLE and the moment I saw it I fell in love with it. It was based on a Paul Gallico story, about St. Francis of Assisi. This was a ninety-minute movie, and they wanted me to write the score in nine days. Nine days from the moment I first saw the picture until I had to be on the recording stage! This is without any preparation, not having read the script, not having seen it before. If I had wanted to spend time thinking about what to do, or designing material, it would have taken up those nine days! Well, I said that I’d love to do the picture, but I cannot and I will not try to do it in nine days. So, lo and behold, they gave me almost fifty percent more time. That means I had thirteen days in which to write the picture! Percentage wise that’s a lot, but it’s still less than two weeks. My usual rule of thumb when I do a theatrical feature is to try to do about ten minutes of finished screen music per work week. Well, you can imagine when you have a total of thirteen days how you’re going to write the complete score! But I loved the thing so much that I said, all right, this time I’ll do it. I’m not going to sleep much for those two weeks, but this is something I’ve got to do. I had one day in which to design all my thematic material, and I was lucky. Every theme I wanted, I happened to hit it right off on the first try and it was right. Now, compare that to the eighteen days I spent on the EXODUS main theme alone, writing pages of revisions, filing, nit-picking, and trying to make it really work right. The time I spent just preparing that theme was more than I had for the whole score for this picture. I also had an orchestrator, which was the reason I ended up with $345, because I had to get help. Orchestrating takes, I would say, two thirds of the time that composing does, usually.

And, last but not least, we get back to money. There is so little money that, first of all, the orchestras are ludicrously small. Most television shows are done with somewhere between ten and twenty men. I remember I wanted to do one thing, which was an outdoorsy action thing; I wanted twenty-nine men and, lo and behold, they gave me the twenty-nine men – once. They had to take it out of the budgets of I don’t know how many other pictures, because the budgets are inflexible. They are set up through what the sponsor pays for these things; I don’t blame the producers. It’s the whole system. There is no question of recouping money at the box office; they get so much money and they have to deliver the goods for that. That’s all there is to It. It’s the whole system of commercial television that causes these conditions.

So you have a very small orchestra, and you have to work at the maximum speed. When I record a motion picture, I do perhaps two and a half minute; maybe if things go well, three minutes per recording hour. Now, a recording hour is actually only fifty minutes because you have to give the musicians ten minutes off the stand each hour. In a motion picture, I record a cue, play it back, listen to the balance, I see whether everything is just the way it should be. On a television show, you must record five minutes of music per hour; otherwise you’re busting the budget again. So you play the first one or two cues back and if that’s fairly decent you just trust the man in the booth. If he gives you the high sign that nothing radically went wrong, you go on to the next cue. There’s no time to listen to it. As a result, sometimes I’ve had very woeful experiences after the orchestra has gone home. I don’t blame the mixer, he’s never heard the music before and doesn’t know what my intentions are. So again there is a tremendous problem in doing a good job.

This all reminds me of the old joke about the young composer going to Richard Strauss and showing him a very poor score and fearing that Strauss would have something bad to say, he said “Master, you don’t know how I sweated over every note, how hard it is for me to write a page of music!” So Strauss looked up in this dry way and said, “If it’s that hard, why do it?” And that is the way I feel about television: why do it? If you have to do it, that’s one thing. If you don’t have to do it, it’s a different business than the motion picture business and I say don’t do it. It’s worse than the old B pictures. It’s a mass production machine that shreds you to pieces. You’re just a cog in a machine, and it is just not for me.

Excuse my verbose answer to the question, but this is a very emotional point for me!

Do you prefer to orchestrate your own scores?

Yes, yes, definitely yes, a thousand times, Yes! The reasons are two. First of all, I love orchestrating. I love the physical act of sitting at my desk, the music is composed, and articulating it for the orchestra. It is a relaxing and exciting part of composing.

Secondly, I think I’m a very good orchestrator, and with very few exceptions I would say when I orchestrate a piece of music it more fully realizes the sound I want. Two exceptions were Eddie Powell, who orchestrated practically all of MAD WORLD; he was a superb orchestrator, and I would say if there was a disagreement between the way I thought it should go and the way he did it, I gave him the benefit of the doubt because his knowledge and mastery of the orchestra was singular. He really got inside the composer’s head and knew just what to do. That was one, and, as I said, Gerard Schurmann, a marvelous orchestrator and master of the medium.

The only reason that I have somebody else orchestrate is if I feel it is such a hassle in the given time that I would hurt, either myself for not being able to get enough sleep because of the hours required to write the orchestration in addition to the composition, or hurt the score which I wouldn’t do in any sense. I don’t mind getting up at four in the morning and working until eleven o’clock at night, but, especially if it is the kind of score that is slow-to-orchestrate, like a big action picture with thousands of notes and a large orchestra where everybody is doing a lot of things, I will use an orchestrator, but only in extreme cases. By and large, if I find that I have a great preference in orchestrating my own music.

You’ve said that “an artist cannot write relevant motion picture music today unless he is involved in the many other forms of music making outside the motion picture field.” How did you feel your experience outside of films has benefited your composition for the screen?

In many ways. First of all, writing for the concert stage has given me a command of form – of large forms. Now there’s nothing like the command of large forms to score a motion picture. Because, if you can make the form in itself express what goes on, on the screen, knowing when to write a fugue, when to write a coda, when to write a development section, when to write exposition (for its dramatic meaning, not for abstract musical reasons), you of course then write music which stands up on its own, and has a much bigger impact while at the same time playing the picture. Moreover, if you’re active in many other areas, you have a much larger area of knowledge to draw from. It’s the same if, for instance, somebody is only a screenwriter. That’s one thing, but if he’s also a novelist and a dramatist and God knows what else – if he’s written for the stage and he’s written for the screen, he has a much greater arsenal of tools with which to attack the task at hand and as a consequence it will be a far more effective job.

I also feel that, not so much nowadays but in the old days it used to be that the people at Paramount were interested in what was going on at Twentieth Century Fox, and the people at Columbia were interested in MGM, and it was sort of an inbred family. It was all the same stuff, but over there, they’re doing this, and here we’re doing that; and I went past that, I went to contemporary opera, for ideas, and to symphony, to chamber music, to experimental things. Knowing what others are doing has a stimulating effect on the imagination; it gives you a vastly increased pallet of colors and ideas of articulations and ways to increase a dramatic thing. The more catholic your tastes are, the more you know about the various demands of music in areas. If you can write for the dance, for instance (which I have done, too), that gives you something. You can suddenly do a comedy scene as though it was a ballet, and that’s a much better comedy than just the squeaks and grunts usually done for television comedy. So, I would say that any experience that you have as a person, and certainly within your profession, can only increase the means at your disposal.

How do you go about transferring your initial ideas into a finished and recorded score?

Well, I’ll have to tell you the little joke about the centipede, who wondered one day how he managed to walk and the moment he thought about it he fell over and wouldn’t move. I’m a little bit in the same position when it comes to scoring a picture. I don’t know how I do it. I guess it’s a gift, to run a scene and to have a musical impulse or reaction to it. The technique, of course, is very cut and dried. You sit in the projection room, you decide where the music goes, you get your timings – I get the picture transferred onto video tape so I can play it here at home – and then I take it scene for scene, and I look at it and ask myself what is the music supposed to do for the picture? Every picture has a basic musical problem. For instance, in some pictures the music is supposed to ride the picture like a jockey, give it pace, give it forward motion; in another picture, you want it to have a unifying effect if the picture is very scattered in the cutting, as MAD WORLD was. In another picture it may be that you have to warm it up; the picture is essentially cold and you have to give the people more feeling and more three-dimensionality so they are not just automatons acting out purely externalized action. And this is different for every picture.

When I get my timings, I watch the scene and I decide on the basic tempo for each cue. A basic pulse that is right – not too fast, not too slow. Now, sometimes of course you will deliberately write music that’s a little faster than the picture, giving the impression that the picture has more pace than it really does, or you want to slow it down if you feel the actors are rushing and they are not giving enough time to let things breathe. Then you write the sketch, with a stopwatch, and then you run the picture again and you read the music. As I read the music with the picture I hear it in my mind as it will actually appear when the music is already dubbed in, and then see what plays and what doesn’t play, and I feel, well, maybe this needs a little bit more emphasis or something more emphatic here, or maybe I should even let the music dropout for a few seconds where I had written something because it will be very effective to have silence and then bring the music back in again, and you get to know each scene intimately. I would say that for a two minute scene, I will sometimes spend three hours running it over and over again until every facial expression and every little innuendo in the voice of the actor becomes apparent to me, and I’ll make notes right on my timing sheets as to where the turning points are, where the reactions are that you cannot see, that are not obvious, so that the music can actually follow the psychological topography of each scene. Or if it’s an action scene, when I will play with the picture and when I will play against it – playing, for instance, something slow and sustained while this furious action is on the picture, which may in certain instances be a more valuable contribution.

By and large, I try to put something in the picture that was not there, rather than duplicate what was there. When it’s all done and I have the particular cue all sketched and the timings are all there and I know exactly where everything will be, and by that time I’ve got a very clear idea also of what the orchestration should be, I’ll either orchestrate it myself or turn it over to the orchestrator. Then it gets copied and I notify the music editor of what aids I need for the recording in the picture, such as streamers or click tracks or a combination – what mechanical aids are necessary in order to synchronize the music with the picture, which is of course run during the recording session.

And that is for the externals. The internals – I cannot really explain why a certain scene makes me feel that a particular form of musical utterance is right and another one is wrong. This is simply my reaction. Why does somebody like spinach and another person hates it, why do some people drink scotch and others drink ginger ale? It’s a question of taste, of association, of personal reactions to certain things. Scoring a picture is a very personal business. I mean, you’re in this thing with everything that’s ever happened to you, with all your personal experiences; with your feelings, your joys and your disappointments. I guess that’s why so few people can really do it, because unless you’re willing to commit yourself and your inner being to do the job at hand, at best it’s going to be wallpaper music.

What’s your view of the current state of film music, what with the resurgence of the symphonic score?

I’m not too happy about the current state of film music, taken as a whole. The reason is not that the composers suddenly have no talent – the reason is that the producers and directors have become heavy handed (with some exceptions that are notable); they are ignorant, primitive. There is almost like a reverting to the approach to movie scoring that was prevalent when sound first came in – using of records and hodgepodge. You know, you write a score and then they decide to add some other things to it. In other words, the rather cavalier way in which the composer’s work is treated these days leaves much to be desired, in terms of the final result.

I think that John Williams has written some excellent scores; I think that Jerry Goldsmith writes some excellent scores. One of the scores that I consider one of the very finest of recent years in every respect – it is a model of subtlety and of just the right tone for the picture – is Dave Grusin’s score for ON GOLDEN POND. It’s beautiful; I wish I had done it! But there’s an awful lot of bad music, and I think the reason is television. Practically all television music sounds alike, it’s squeaks and groans and electronic effects. It works fine for the junk that is usually on the tube, but it’s not really an art, and motion picture scoring can be an art. But many people in the picture industry have either come from television or that has set their standard, and I think the whole profession has been dragged down to a low that was rather unknown, say, twenty or thirty years ago. And there are very, very few people that really do a great job. I think the resurgence of the symphonic score has been very, very nice; but on the other hand I also find that the composers called upon to do this don’t have the background now, having come either from rock and roll or from some very minor things. You see, I came to Hollywood in the heyday of the symphonic score and as I learned how to deal with a motion picture I had these marvelous people, the examples of Alfred Newman, Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann, even Victor Young (whom I didn’t like because he was too sweet for me, but in a way what he did worked). But nowadays, whom have you got? You’ve got to kind of start the world from scratch. So I think, by and large, the current state of film music is not what I would like it to be, but maybe after a while it’ll get better again as a body of work begins to make itself felt which gives people something to shoot at.

Your latest score was for TWO IN THE BUSH. What sort of approach did you take for this film?

This film made a very, very minor effort to go towards a little more emotion than most action pictures; it’s an action comedy, about a rally taking place in Africa. So, you’ve got a lot of driving, you’ve got the jumping cars, you’ve got some comedy, but there’s also a little love interest. So what I wanted the music to do, aside from supporting the picture in its various exploits, was to warm up the characters, to give a little feeling to them so they’re not just puppets driving cars, but they’re people who are involved personally as well as just in an external venture. So, my music was essentially an attempt to lend a little warmth to a picture which otherwise would have just been a pure action picture. But, of course, you can’t put it in a scene where it wasn’t there; I mean, the love scenes such as they were perhaps came to a total of three or four minutes in the whole picture. But I spent a lot of thought and effort on those. I spent over a week designing a love theme that really would convey a feeling and be right for the characters, because I felt those little rest points from the madcap action would really be important.

What are your current activities in the film music field?

TWO IN THE BUSH was my last assignment, and at this moment I’m kind of taking it easy. I told my agent that I really don’t want to do any more of these ridiculous action pictures with car crashes and cars jumping through the air which are so prevalent now, and I don’t like real violence either. There are a lot of pictures being made right now that are pretty mindless, they’re either the bloody horror things or they are what I call athletic pictures. I’m a very people oriented composer and I do my best work when I have relationships between people, conflicts within people, feelings to express. These are all dirty words in the picture business right now, and as a consequence there’s a glut of the other type of work being offered, and I just don’t want to do these kinds of things. And since I don’t have to do everything that comes along I’ve given my agent strictest instructions to reject these offers and wait until something comes along that really means something.

How do you musically approach a film that is concerned with characters and relationships, such as THE RUNNER STUMBLES?

If the film deals with relationships it dealt with feelings, and feelings of course are a great domain of music. So you can write music which has emotion, which moves the audience emotionally, rather than just providing kinetic energy. This is more satisfying, and you can also get inside your characters. You don’t just play what’s on the screen; you can play what’s going on in the characters. But nothing much is going on in the characters if they just race cars and pull guns. There you play an external situation, and I find that it’s more exciting and more gratifying, and musically more effective, to have subject matter for which music is singularly well suited.

You know, it’s interesting that two recent films notable for dealing with conflicts in relationships – KRAMER VS KRAMER and ORDINARY PEOPLE – utilized no original music but classical works instead. What’s your view of this practice?

I have a one-word answer: dim! Producers always get bright ideas when it comes to music (thus the old joke: everybody has two jobs at the studio, his own and music!), and they say “I want to do something different, how about using records, how about doing this, how about doing that?” They think they do something good for music, but actually they’re putting music back to where it was in the silent days, when indeed nothing but well-known selections were played. I think it is a dreadful practice, I think it hurts the picture. I would never in a million years, if I were a producer, have a classical score except maybe on a very, very special picture where it is really right.

But I wouldn’t use classical music as a score, I think it interferes. If you know the music, it draws more attention to itself than it should because it’s a known work. If you don’t know the music, it doesn’t support the picture because it wasn’t written for the picture. So it really shows a woeful underestimation of what a good score can do, and that comes in part from the fact that so much bad stuff is all around us. Producers and directors, like everybody else, watch television. They hear the kind of junk that television produces, musically, and they say “oh, that’s original music, I don’t want that in a picture!” I don’t blame them.

I’ll give you an example. The picture 2001 was to have had a score by Alex North. Mr. Kubrick in his infinite wisdom refused to show the picture to the composer, and instead gave him one reel and told him to go ahead and write a score without knowing what was going to happen or what the whole meaning of the picture was. Alex wrote a score, Mr. Kubrick said, “No, that’s not what I want,” and proceeded to make the worst pastiche by using records. I found, for instance, the famous scene where the module lands in the mothership, where they played the Blue Danube, to be a textbook case of bad scoring; I think it destroyed the scene. And people said, “Well, he must have meant something, that was some kind of brilliant stroke”. I thought it was pure, unadulterated nonsense – stupidity and arrogance! Somebody once said that there is such a thing as the arrogance of ignorance, and I think that is really what results in these scores from classical works.

I think the classical works are marvelous pieces of music that should be performed as concert works, and I think movie music should be performed as movie music in a movie, and I don’t think the twain should meet except in very, unusual cases, maybe one picture every twenty years would be right. I think that both KRAMER VS KRAMER and ORDINARY PEOPLE would have been more affecting with a fine score (and by fine score, I don’t mean the kind of junk you usually get) by a real composer of which there are many around. But to use Vivaldi or something like this is sheer nonsense, and I am dead against it. I think it puts movie music back, and I think it is a disservice to the director’s own picture.