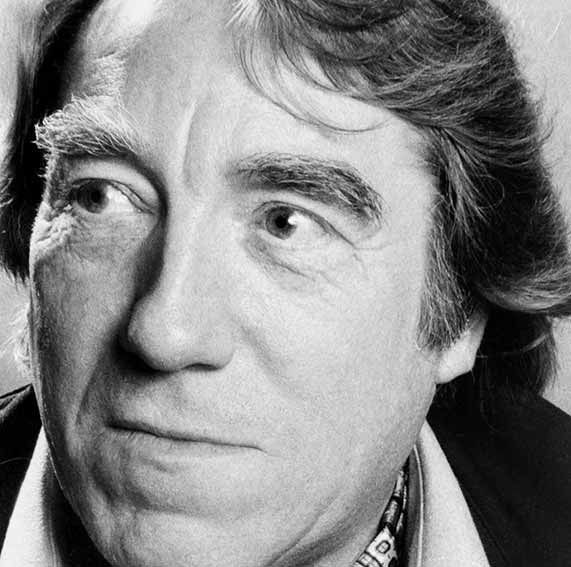

Hugo Friedhofer

Source: Films in Review Vol XVI No 8

Publication: October 1965, pp 496-502

Publisher: National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. Copyright © 1965 All rights reserved.

Visit the representative website of Hugo Friedhofer - Go to site

“I think Friedhofer has a better understanding of film music than any composer I know. He is the most learned of us all, the best schooled, and often the most subtle.” Thus David Raksin, himself a respected veteran writer of film music. Although Raksin’s sentiments are shared by many Hollywood musicians, Hugo Friedhofer’s name is practically unknown to the movie-going public. To explain Friedhofer’s lack of fame Raksin proffers this: “Virtue may be its own reward, but excellence seems to impose a penalty upon those who attain it. Composing something that isn’t a repetition of what’s been done before, cultivating differences from others, seeking out what is special, requires extra effort, extra time, and a little more indulgence from producers. Those who want scores ‘not good but by Thursday’ often prefer to promote men whose qualification is that they deserve it less.”

Hugo Friedhofer arrived in Hollywood in July ’29 and has composed the scores of some 70 films. He also contributed to the scores of 70 others. Indeed, he has worked as collaborator, adapter, arranger, orchestrator and utility composer* on more films than he can remember and in the highly specialized field of orchestration Friedhofer is regarded as The Master. He orchestrated more than 50 Max Steiner scores, and was the only man Erich Korngold fully trusted to touch his music (he orchestrated 15 of Korngold’s 18 film scores). Friedhofer’s film music activities have been so various it is impossible to compile a complete list of all the films he has worked on.

Friedhofer has not gone unrecognized by his peers. His score for THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES won an Academy Award in ’46, and he was nominated for an Oscar for eight other scores. He himself thinks a nomination is more of a recognition than an Oscar, since a nomination results from the votes of composers and an Oscar from the vote of the Academy’s whole membership. The scores for which he was nominated, in addition to THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES: THE WOMAN IN THE WINDOW, THE BISHOP’S WIFE, JOAN OF ARC, ABOVE AND BEYOND, BETWEEN HEAVEN AND HELL, BOY ON A DOLPHIN, AN AFFAIR TO REMEMBER and THE YOUNG LIONS. This list does not include the score Friedhofer values most, that for ONE EYED JACKS, Marlon Brando’s pretentious and unsuccessful Western.

Friedhofer was born in San Francisco on May 3, 1901, and was the son of a cellist. His father had also been born in San Francisco but had taken his musical education in Dresden, where he met his wife, also of a musical family. Friedhofer dropped out of school at 16 - he had been an art major - and got a job as an office boy. Later he worked in the designing department of a lithograph firm, and at night studied painting at the Mark Hopkins Institute. He recalls a voracious appetite for reading, which, along with his feeling for art, are quite apparent on entering his Hollywood Hills home today. One entire wall of his living room is a bookcase, and paintings are in every room.

His father had started him on the cello when he was 13, but it wasn’t until he was 18 that his interest in music predominated over his interest in painting. Once he had chosen between the two he studied seriously and within two years was able to earn his living as a musician - casual engagements at first, then steady work in movie theatres, two years with The People’s Symphony, which had been set up in opposition to the San Francisco Symphony, and, in ’25, a berth with the orchestra of the Granada Theatre, which Friedhofer describes as “one of that decade’s most ornate film cathedrals.”

It did not take Friedhofer long to realize that he had more interest in what the other instruments were doing collectively, i.e., in orchestration, than in being a performing cellist. And so, concurrent with his various jobs as a cellist, he studied harmony, counter point and composition with the Italian teacher-composer Domenico Brescia, a graduate of, and fellow pupil with Respighi at, the Conservatory in Bologna. Brescia later became head of the music department at Mills College, a post he held until his death in ’37. Friedhofer’s studies stretched over a five year period, at the end of which time he was able to put aside his cello and obtain work as an arranger for stage bands.

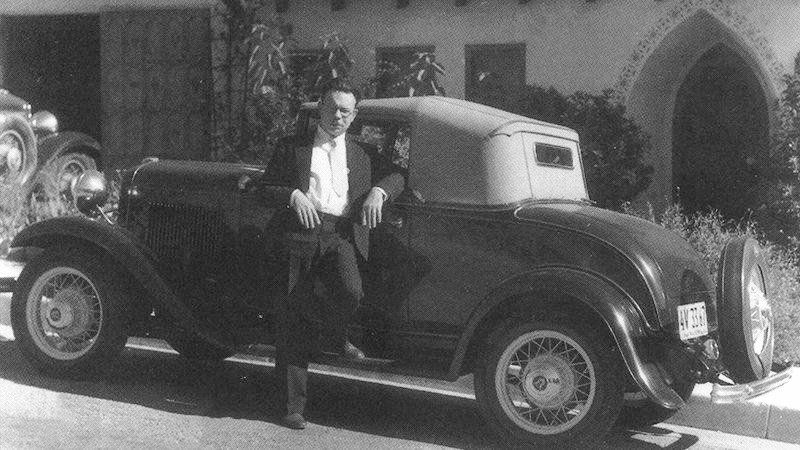

By that time sound had come to the movies and a violinist friend, George Lipschultz, who had become music director at the Fox studios, offered Friedhofer a job there as an arranger. The first film on which Friedhofer worked was the musical called SUNNY SIDE UP, and he stayed at Fox for five years, until it merged with 20th Century. Then, after a few months of free-lancing as an arranger, he was hired as an orchestrator by Leo Forbstein, head of the music department at Warners.

Under Forbstein’s astute command Warners maintained the most formidable musical group ever assembled by a film studio. Its stars were Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, Franz Waxman, Adolph Deutsch and several other excellent musicians, and Friedhofer hoped he would soon be one of them and compose his own scores. But throughout the eleven years he spent at Warners he was not given one assignment as a composer. Forbstein realized Friedhofer was a superb orchestrator and paid him liberally to orchestrate Korngold and Steiner scores.

“Forbstein was no musician to speak of,” Friedhofer says, “but be was a good executive and organized Warners’ music department so well it could practically run itself. We were all cogs in his well-oiled machine. I was servicing Korngold and Steiner to everyone’s complete satisfaction, so why change things? Working conditions were good, I was well paid, and I suppressed my creative ego until I could do so no longer.” However, in between Korngold and Steiner assignments, Friedhofer was occasionally able to do work for other studios, and in ’37, through Alfred Newman, for whom he had worked at Fox, Friedhofer was commissioned by the Goldwyn Studio to write the score for the Gary Cooper vehicle called THE ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO.

Friedhofer’s first full-length score is a fine piece of work and was well received by Hollywood musicians, but Friedhofer did not get another chance as a composer until ’42. Forbstein, who was interested in Friedhofer only as an orchestrator, did make two concessions: he raised Friedhofer’s salary, and gave him a screen credit. Friedhofer’s first Warner credit was on Korngold’s THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD. Of Korngold Friedhofer has this to say: “His contribution was enormous and he influenced everyone working at that time. He was the first to write film music in long lines, great flowing chunks, that contained the ebb and flow of mood and action, and the feeling of the picture. Of course his assignments - those gorgeous spectacles - were pushovers for his kind of music. Some critics thought he lowered himself by writing for films, but he didn’t think so. He was excited by the medium.”

What Friedhofer learned from Korngold or Steiner he was able to translate into his own musical language and his music doesn’t sound at all like theirs. As do most Hollywood composers, he has a special affection for Steiner. “Real film music began with Max,” Friedhofer says. “Many of the techniques were invented by him, and many of his devices have become common practice. His is true mood music, unobtrusive background that is also connective tissue, subtle and sensitive.” Steiner is not always accurate, however. Friedhofer considers THE CAINE MUTINY score little more than a musical recruiting poster for the Navy and says it misses the point of the film (i.e., Queeg’s neurosis). Steiner’s much heralded music for THE TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE also gets a low rating from Friedhofer. He thinks pre-Hispanic Mexican musical themes should be used in films about Mexico, not music with Spanish idioms. He also says Steiner’s TREASURE music “didn’t match the barrenness of the landscape or the stark tragedy of the protagonists. The score was all wrong - I can lie about almost everything in the world except music.”

Steiner had once been an orchestrator and knew the value of Friedhofer from personal experience. He would indicate in his sketches the effects he wanted and leave it to Friedhofer to fill in. In his first ten years at Warners Steiner scored an average of eight or nine pictures a year, and the success of this large volume of work is partly attributable to Friedhofer. Steiner wrote the score for GONE WITH THE WIND (three hours of music), the background music for Intermezzo, and “Symphonie Moderne” for FOUR WIVES, all within a period of twelve weeks. He claims to have been taking benzedrine through it all. Friedhofer worked closely with him on GONE WITH THE WIND, developing thematic material and injecting a few fragments of his own.

The need for the orchestrator in film music is obvious and snobs in other areas of music who sneer at film composers who “aren’t capable of doing their own orchestrating” are absurd. A composer like Korngold would hardly have employed an orchestrator had it not been a matter of time. When Friedhofer scored THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES he used several orchestrators, and he has orchestrated few of his own scores since. Friedhofer claims a musician either has a knack for orchestration or he hasn’t. He says the same about his own ability to look at a film and know immediately what it needs musically. Friedhofer also has a wider sense of music than any other composer writing for films, and can place himself musically in any geography, and, without actually quoting local material, simulate the musical color of any environment.

His score for THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES is honest Americana; that for VERA CRUZ, is vigorously Mexican; his music for BOY ON A DOLPHIN is suggestive not only of the beauty of the Greek islands but also of the sensations of diving in water. In THE SUN ALSO RISES he captured the spirit of post World War I Paris as well as the pageantry of the festivals in Pamplona (he says the score for SUN was his most difficult technically). He wrote a delicate love theme in an Indian mode for THE RAINS OF RANCHIPUR, and an entirely different kind of Indian music for the excellent Western called BROKEN ARROW. He suggested medieval England in THE BANDIT OF SHERWOOD FOREST, and turbulent France in JOAN OF ARC. For THE YOUNG LIONS he wrote a score that is militant and savage yet devoid of bravura about the glory of war. There is not any kind of film Friedhofer hasn’t scored.

Queried about his style, Friedhofer squirms and denies he has striven consciously for a personal style. He thinks of himself as being in the mainstream of modern music “but not far out.” He was schooled in the German masters, grew up in the jazz-impressed ’20s, and is particularly fond of Spanish, Mexican and Latin music (why, he doesn’t know). His friends say he has recognizable musical characteristics and that his style is noticeably mordant. Frederick Sternfeld, of the music department of Dartmouth, has analyzed several Friedhofer scores for his classes and come up with chatter about “Hindemithian quality” and “a lineal dissonance.” With characteristic bluntness Friedhofer says of his film scores: “I write ’em as I hear ’em. When I walk into the studio I’m not an artist so much as a plumber.”

As are all film composers, Friedhofer is constantly being asked for his definition of film music. He dislikes such pontificating and says there is no definition. But, when pushed a little, he will say film music should be governed entirely by the visual, and that each picture has its own needs. It is absurd, lie says, to assume that music must always be in the background, for there are times when music can step out or should be dominant. Most of the time it can’t and would defeat its purpose if it did. Friedhofer agrees with Virgil Thomson’s advice to a young composer: “Never make the mistake of over estimating an audience’s taste, but don’t under-estimate its intelligence either.” Friedhofer thinks this especially applies to film scoring. He also feels film music has had an effect on the concert hall, if only because many have subliminally absorbed contemporary musical idioms from films without being aware of it and are therefore receptive to modern concert pieces they wouldn’t accept had film music not prepared the way.

In the perpetual war between producers and composers Friedhofer has fared well, and has had less music scrapped than his colleagues. “Possibly,” he says, “because I’ve been chicken, and gauged the calibre of my man before hand.” He sympathizes with producers because their job forces them to act omniscient. “The omniscience of producers isn’t taxed as much in the fields of writing, photography and acting as it is in music, which seems to be a closed shop to them,” says Friedhofer. “In many instances they are forced, in order to save face, to assume a profundity about music they don’t possess.” Film music, he adds, must not be compared with concert music, for its purpose, and therefore its texture, is different. Producers, like the public, are usually unmindful of this.

Friedhofer does not agree with those who say film music composers are never given enough time. Composers of the baroque and pre-classic era had to work fast, he points out, and were forced to turn scores out regularly whether they felt like it or not. They, too, had no time to second guess. When Papa Haydn got another order from Prince Esterhazy he first knelt in prayer, then spat on his hands and wrote another masterpiece. Film composers should have a similar attitude, even though their chances of turning out master pieces are less, due not so much to lack of genius as to the fact that a film composer’s work is always determined by the nature of the film, obliging him to curtail material he might like to expand.

Friedhofer has no regrets about being a film composer: “A strange snobbery toward this business exists, but it exists largely among composers who haven’t been asked to write music for films,” he says. But Friedhofer does write concert pieces and constantly studies musical theories with which he doesn’t agree and listens to music he doesn’t enjoy (“I like to hear what the enemy is up to”). As late as ’54 he took a refresher course in counterpoint at USC. He believes writing film music would benefit any composer. The time factor, he says, is excellent discipline and forces a composer to say what he has to say trenchantly.

Friedhofer has been married twice, and had two daughters, one of whom died of leukaemia in ’55. He is a man of considerable humor, and his comments are much sought after at parties and gatherings of musicians. He is a-political. Although associated with film music since the screen acquired sound, he has no intention of quitting movies and retiring. At 63 he is healthy and alert, and is aghast at any implication he is a senior citizen. And he is rather pleased to be regarded as the kind of composer other composers turn to.

* The terms “adapter” and “arranger” often intertwine. To adapt is to tailor a piece of music composed for another purpose - e.g. a part of a symphony - in order to make it fit a scene. To arrange is to change the clothes of a piece of music - something scored for one instrument or one vocal range is arranged so it can be performed by another instrument or vocal range, a sonata can be “arranged” into a concerto, a melodic sketch into something bigger. This last involves orchestrating of a kind that makes use of an orchestrator’s own inventions (Morton Gould making a 5 minute rhapsody out of a Jerome Kern song). Friedhofer’s film music orchestrations were not of this kind. He executed a composer’s instructions, and a Korngold score came out sounding like Korngold, not Friedhofer. But whenever lesser composers provide merely one-note melodic lines. Friedhofer, in building these into orchestral pieces, would utilize his own inventiveness.